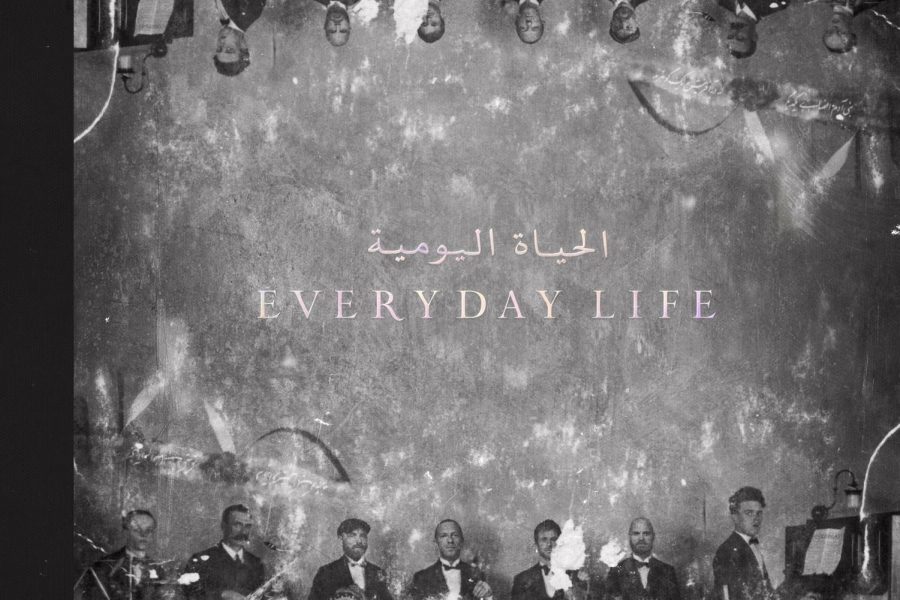

Review: Everyday Life breathes life into Coldplay, at least

Dec 9, 2019

Has the Trump presidency killed the protest song?

The last time America had a Republican commander-in-chief the music industry turned thoroughly political. Songs that weren’t explicitly anti-Bush were anti-war, anti-media, anti-fascism. Green Day’s punk rock opera American Idiot is probably the most prominent example, but from about 2002 to 2007, artists everywhere released protest music that ranged from sneeringly caustic (The Thermals’ “Here’s Your Future”) to heartbreakingly gorgeous (Josh Ritter’s “Thin Blue Flame”). And regardless of your personal beliefs, it makes sense that the current president’s far-right policies and divisive rhetoric would move songwriters to action in the same way that, say, Bush’s invasion of Iraq did. Yet nothing from the past four years has shown nearly as much staying power as American Idiot or its ilk. It might be that politics have so inundated every part of our lives that we look to entertainment as a reprieve, not a rejoinder, which is the basis for a lot of the criticism that gets leveled at Saturday Night Live. There might be a deeper reason.

You may be thinking that it’s weird and probably inadvisable for this Coldplay piece to get so political. Fair enough. That’s the same reaction I had when I listened to Everyday Life, the band’s eighth album.

Let me explain. I think protest music has shrunk not in incidence but in scope: As pop culture becomes more diverse, increasingly non-white, non-male, non-straight artists are free to write songs that are deeply personal. John Lennon could write “Imagine” because he didn’t have to deal with adversity any more specific than the universal problem of war. Kendrick Lamar probably could have written “Imagine” too, but there’s a reason To Pimp A Butterfly isn’t about peace on Earth. Whether an industry that is no longer firmly the straight white man’s has any place left for his protest music is the central question of Everyday Life.

Coldplay, and its singer, Chris Martin, usually refrain from overt politics, barring a thinly veiled swipe at Fox News on their 2008 album Viva La Vida. So Martin tries a couple things to make his songwriting resonate, with varying degrees of success.

Take co-lead single “Orphans.” Martin hasn’t lost his ear for melody or his penchant for choirs oohing, so it’s catchy as anything. The lyrics focus on a Syrian refugee named Rosaleem who yearns for life to return to normal, singing, “I want to know when I can go / Back and get drunk with my friends.” Martin has said his intent in writing “Orphans” was to emphasize that refugees are people above everything else. That point is well taken. But writing a song about the Syrian Civil War and making its chorus about getting drunk feels a little trivializing and a little gross.

In the same vein, “Daddy,” a muted piano ballad from the perspective of a child whose father is absent or missing, is too uneven to land fully. Part of that comes from Martin’s tendency to toy with understatement and then go one step further: “Look, dad, we got the same hair” is a genuinely affecting line, but it’s followed by “And daddy, it’s my birthday,” which is almost comically Dickensian. As in “Orphans,” part of the unevenness is a function of the shift in perspective. (Although I’m trying to figure out why songs like Suzanne Vega’s “Luka” and Pink Floyd’s “Mother” retain their power despite similar perspective shifts, and it might just be that I’m not entirely comfortable with a middle-aged man singing “daddy” over and over.)

Coldplay executes the same trick much more effectively on “Trouble In Town,” the third song on the album. Piano and a quietly propulsive bassline drive Martin’s musings on racial inequity (“Because they cut my brother down / Because my sister can’t wear her crown / There’s trouble, there’s trouble in town”), but after a couple verses, the music drops, ceding center stage to a 2013 recording of two pedestrians who were racially profiled and harassed by a Philadelphia police officer. As the officer in the recording snaps, “You ain’t talking to me that way,” the band erupts with a fury that feels spontaneous and that, for the first time in a long time, recalls the high-water mark of their 2002 album A Rush of Blood to the Head. Crucially, “Trouble In Town” lets its subject speak for itself. Martin can relate it thematically to his own perspective, but he knows enough to know that he doesn’t know enough, and the music that results is powerful without being patronizing.

The second thing “Trouble In Town” does well is give Coldplay room to breathe. Space and silence are necessary parts of music, but they’ve been underutilized: Listen to the first 15 seconds of anything Coldplay released this decade and you know at once how the rest of the song will play out. In general, Everyday Life is the most intimate the band has sounded in years, buoyed by a warm, crackling production and an expanded palette of textures. One of Coldplay’s strengths is a consistent willingness to push their music forward, and so it’s a relief that the blandly pleasant dance-pop they’d been inching toward since 2011’s Mylo Xyloto has fallen out of favor, because it allows the band to draw on their more emotive alt-rock (or, if you prefer, “Radiohead-lite”) origins without regressing toward them. A fair number of the songs dip entirely into other genres, like the gospel-tinged “BrokEn” and 60s-inspired “Cry Cry Cry,” both of which are cleanly executed but don’t add a lot to the music they take inspiration from. It’s when Coldplay uses genre and cultural flourishes to accent their own style that the experimentation is most successful, like co-lead single “Arabesque,” which spins a galloping Middle Eastern beat into a saxophone breakdown into an orchestral climax to dizzying effect.

Many parts of Everyday Life treat everyday life with a broader lens. These are the tracks that hew closely to the straight white male form, the tracks that could have easily come out of the Bush administration. “Guns” opens the second half of the album with the most traditional protest song Coldplay has ever written. It pulls the same lyrical imbalancing act as “Daddy” in jumping from “All the kids make pistols with their fingers and their thumbs / Advertise a revolution, arm it when it comes,” which could be a withering indictment of decades of U.S. foreign policy, to “War is good for business, cut the forests, they’re so dumb,” which is the same thing stripped of any nuance. But “Guns” is far more effective than “Daddy” because it is far more immediate. For one thing, Martin is singing from his own point of view. For another, the song, stripped down to vocals and guitar, lays bare the tension too frequently buried by Coldplay’s sparkling production. That tension is a welcome change. When Martin, a traditionally family-friendly frontman whose band once rejected a song he wrote about drinking because they didn’t think he was cool enough to sing it, snarls, “Everyone’s going f—king crazy,” it’s hard not to be thrilled.

“WOTW / POTP,” one of the album’s many brief interludes, finds Martin mumbling platitudes like “In a world gone wrong / How can I be strong?” “Champion Of The World” is another indie rock anthem full of feel-good lines like “She’ll pin the colors and say / ‘I wandered the whole wide world but baby, you’re the best.’” (In the Coldplay Extended Universe, “she” is a nameless, featureless girl who shows up a couple times an album to mutter something confusing and vaguely inspirational.)

But if there’s plenty of reason to doubt the case for another “Imagine,” the closing track, “Everyday Life,” makes a persuasive counterargument. It opens with looped strings, piano, and the wide-eyed oh-my-gosh sentimentality that Martin pulls off with uncanny regularity — “What in the world are we going to do? Look at what everybody’s going through.” He avoids the pitfalls of “WOTW / POTP” by acknowledging his own place in the world gone wrong, asking, “How in the world am I going to see you as my brother, not my enemy?” It’s a fine exercise in nuance from a topic that desperately requires it.

In the middle of “Everyday Life,” the orchestra swells, and Martin gives us something approaching a thesis: “You’ve got to keep dancing when the lights go out.” I think that’s the key to this album. Everyday Life is frequently clumsy but always sincere, even if it can’t live up to the ambition of its title. As with most artists, Coldplay is at their best when they’re just being Coldplay, and that, if nothing else, is a welcome return.