In the winter months, the Tumen River that snakes between China, North Korea, and Russia freezes over and becomes almost indistinguishable from the barren, snowy landscape surrounding it. The river bank appears devoid of life — even the weeds that sprout through the snow are dying, and the trees stand bare in the cold.

Around 15 years ago on March 17, 2009 — St. Patrick’s Day in the U.S. — Chinese-American and Korean-American journalists Laura Ling, then 32, and Euna Lee, then 36, found themselves on this river.

It was the women’s and their producer Mitch Koss’ last day in China working as editors and producers on a documentary about North Korean defectors for Current TV, a cable network founded by former Vice President Al Gore. Ling said that Gore’s network was unique, as it encouraged reporters to cover international news stories in person, a practice that had been declining in past years.

That day on the river, the group was with a “fixer,” someone Ling described as “a local guide in the area who had worked with other media entities before, to help them with the story” on an episode of NPR’s Fresh Air.

“[We were on the Tumen River] to film the route where the defectors escape. We just wanted to get the atmosphere to show the viewers what these defectors are going through,” Lee said.

Their fixer led them onto the frozen river. Ling recalled being suspicious, but the group ultimately followed him to the North Korean river bank. The fixer pointed to a faraway village and began to make low hooting noises, which Ling and Lee assumed were to communicate with his North Korean soldier connections.

“We quickly recorded the footage and then left the river. We were there for about a minute,” Lee said.

When they were halfway across the river, headed back towards China, Koss suddenly shouted “Soldiers!” The group saw two little soldiers with rifles running across the bank and over the river.

“So we all ran as fast as we could towards Chinese soil — and we arrived there… I saw Laura fall on her knees. My fixer asked us to just keep running, but I couldn’t leave her there alone,” Lee said. “I asked her, ‘are you okay?’ and she told me, ‘I can’t feel my legs.’”

Before the women knew it, the soldiers were surrounding them. Lee began struggling with the soldiers, and in the chaos, Ling was hit in the head by the butt of a rifle. She immediately lost consciousness.

The two soldiers dragged the women from China, across the icy Tumen River, and into North Korea, where they began their nearly-five month detainment.

The Tumen River is considered one of the most dangerous places in the world by World Help, a Christian humanitarian organization. Although it’s not particularly deep, wide, or fast-moving, nearly every square mile of the river is being watched by Chinese military jeeps or North Korean soldiers hidden in huts along the shore. There is no fence that separates the countries and there are no signs that warn people they are about to cross national borders. But everyone who comes to the river knows where they are. During the day, the river serves as a clothes-washing spot for locals, but at night, it becomes an escape route for North Korean defectors, the same ones that Ling and Lee were attempting to document.

Defectors are defined by Merriam-Webster as “a person who abandons a cause or organization usually without right.” North Korean defectors leave the country for many different reasons, including hunger, poverty, and dissatisfaction with the current political situation.

As stated by an article from NK News, an independent newspaper that focuses on North Korea, 80 percent of defectors are women and most defectors come from the regions along the borders of North Korea, along the Tumen and Yalu Rivers. NK News reporter Tae-il Shim guesses that this is because the punishment for defecting women is less harsh than the punishment for men and because women face more responsibilities and hardships as the main provider for their families in some regions.

In order for defectors to escape, they often use a broker, or someone who facilitates their journey out of North Korea for a fee, according to an article by CNN.

“When they cross the border, without knowing it they are to become prey to these smugglers [brokers] and [victims of] human trafficking,” Lee said.

When they arrive in China, the women, who are often young, are sold to bars for entertainment, forced to become cybersex slaves, or bought by poor Chinese farmers to serve as their wives, amongst other fates. Due to China’s one-child policy that was in place for 35 years, the country faces declining birth rates and a scarcity of females. Chinese farmers can’t find Chinese women to marry, so they turn to vulnerable North Korean defectors.

“We thought this was a very important story to highlight and let the world know. Then hopefully, these female defectors understand what they are getting into when they seek a better life or freedom,” Lee said.

Ling and Lee shivered as they walked.

“I asked Laura, ‘can you pray? Pray with me, I know there’s a bigger power there who can protect us,’” Lee said.

The two prayed quickly.

In the scuffle with the soldiers, Lee had left her coat on the frozen river. She had remembered there were a couple of phone numbers of defectors in her pockets, which she didn’t want the soldiers finding.

“They walked us to the post, and I remembered I had a tape and I had a small cell phone that I used in South Korea, which could endanger people who we interacted with,” Lee said. “So on the way there, I slowly dropped them, one by one, in the bushes.”

The women were taken to a jail along the Chinese and North Korean border. While there, Ling also had to dispose of materials she was carrying. She was carrying a notebook full of questions she asked defectors in China.

“Those questions could have been interpreted as being critical of the North Korean regime,” Ling said. “I swallowed some of the pages to try to get rid of that information because I was so scared that it would be interpreted the wrong way.”

After spending a couple of days in the jail, the women were driven to a detention center in Pyongyang, the capital of North Korea. This journey took several more days.

Upon arriving at the new facility, Lee and Ling were separated. They wouldn’t see each other until their release, almost five months later. Lee said she was interrogated by North Korean investigators from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m., six days a week. Ling, who experienced the same, recalled trying to convince the investigators that she wasn’t a spy. The women had originally said they were students working with a professor to learn about the economic conditions along the Chinese-North Korean border, but the investigators eventually disproved their claims.

“The interrogator wanted to find out every single thing about my personal and work life,” Lee said. “They were very upset that we were working on the documentary. They didn’t want us to show the dark side of North Korea.”

When the women weren’t being interviewed, they were alone in separate small rooms, consisting of a bed, a desk, and a bathroom. Two female guards would watch over them at all times and feed them three meals a day: a simple dish of rice, soup, vegetables, or fish. Later on, they would be able to take one 30-minute walk outside per day.

“When you are alone and have no one to talk to, nothing to read, time goes by so slowly. One day felt like one year,” Lee said.

“I definitely prepared myself mentally to spend a long time in North Korea — to not see my family or my husband again,” Ling said. “But at the same time, I knew that I was also a political pawn.”

To cope with her fear and depression, Ling practiced meditation and yoga and tried to befriend the guards. She said they were young women who spoke a bit of English and were curious about American culture.

“These women were the only consistent human connection I really had,” Ling said. “They showed me small acts of kindness and I showed them a lot of gratitude, which I think they appreciated. We developed a different, broader perspective of each other, coming from these two very different countries.”

Lee also found amity with the guards. Even though she wasn’t supposed to interact with them, she taught the women a couple English words. She remembered one of them loved to belt “My Heart Will Go On” by Celine Dion, over and over again.

“I grew up in South Korea thinking that they were our enemy,” Lee said. “But when I saw them, I found humanity in these people that gave me hope that maybe all this hatred, this distant misunderstanding that we built through media or news that we’re watching can [disappear].”

After a few months of interrogations, North Korean officials brought Ling and Lee to trial. The women were sentenced to 12 years of hard labor.

Liberty in North Korea (LiNK), an international non-governmental organization that helps North Korean refugees escape the country, considers the nation the most authoritarian in the world. According to LiNK’s website, North Koreans cannot leave the country without the government’s permission, make international phone calls, watch a TV program that has not been approved by the state, or access the internet at all.

Additionally, people who can leave the country, such as diplomats, elite students, and athletes, are banned from speaking to South Koreans and limited in their communication with foreign people they meet. They are required to attend ideological training once they return to ensure that they still wholeheartedly support the North Korean government, and have not been distracted by systems from nations, like capitalism.

In North Korea, defecting is a crime that yields an extreme lifetime of punishments, if caught. These punishments can involve execution and deportation to detention centers and labor camps, where defectors report being beaten, starved, and isolated, Business Insider wrote. China considers North Korean defectors “economic migrants,” which means if they are found, they will be forcibly deported back to North Korea, according to an article by CNN. Then, their fates are in the hands of the North Korean government.

Ling and Lee were horrified once they heard their 12-year sentence. But, they were never actually taken to a labor camp. Laura had been hit on the head with the butt-end of a rifle. Authorities evaluated the women and put them in medical isolation until they were strong enough to work.

While the women waited to be sent away, they were beginning to receive letters from their friends and family, who had been notified about their imprisonment.

Koss, the Current TV producer, had alerted an American embassy after running away from the Tumen River. Within a week, the world was fighting for Ling and Lee.

“People rallied around our story in the most amazing way,” Ling said. “I read about various vigils and rallies [for us] that were taking place in the letters I was sent. It really helped sustain me and keep me hopeful.”

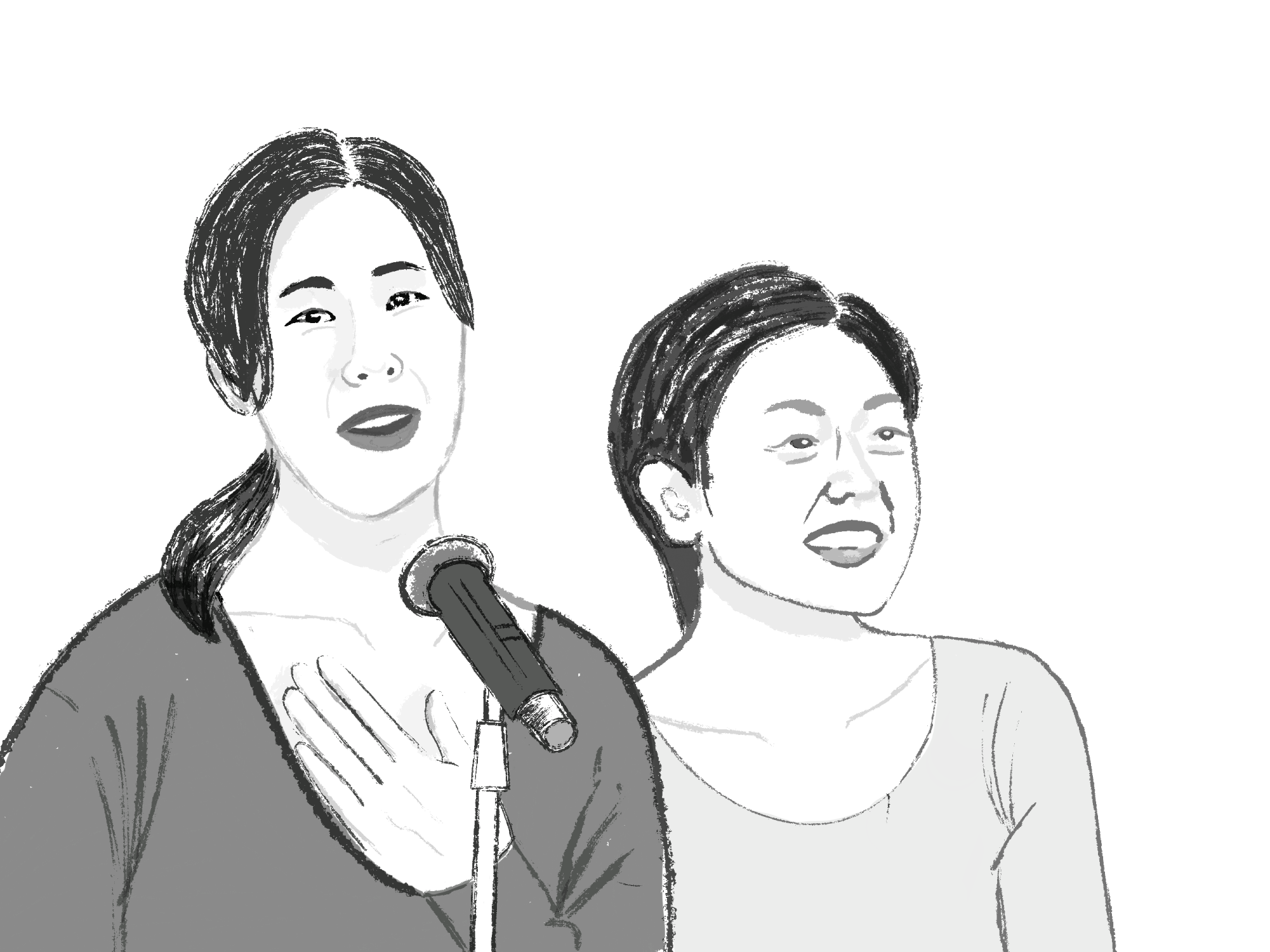

Lee said she was thankful to receive a lot of recognition for her hard work as a journalist. While Laura Ling’s sister Lisa Ling was a journalist known for her work with “The Oprah Winfrey Show,” National Geographic, and “The View,” no one really knew Lee’s name until her detainment.

“I was a nobody and then receiving all this support from people who I never knew was a very humbling experience,” Lee said. “It showed me that people really do care about others.”

Lee’s daughter was four years old at the time of her imprisonment. Mothers around the world were sympathizing with her for not being able to see her child for 140 days.

After a couple months, Ling was able to call her sister and her husband, Iain Clayton.

“It’s hard to describe what it felt like to hear their voices,” Ling said. “But, I was also trying to be very strategic in what I said, because I knew that I was only given maybe a minute to talk to them. I wanted to let them know what I thought was necessary to secure our release.”

According to an article by CNN, in one of their phone calls, Ling had told Clayton that North Koreans were willing to release the two journalists if a high-level ambassador were willing to travel to Pyongyang.

Ling’s connections to journalists and government officials, through former Vice President Al Gore, increased awareness of their cause and made their release quicker.

Today, there are so many journalists that are in prison in countries all around the world. Although Ling is grateful to have received a lot of attention, she wants people to remember that she and Euna weren’t the only ones imprisoned.

“It was our fellow journalists that kept our story alive, including Lisa,” Lee said. “The day before we were released, the person who interrogated me — I call them Officer Lee — came back to the place where I was held. He told me there is some good news: ‘someone very important from America is coming to see you guys.’”

Ling and Lee were given few details. They were reunited and taken to a hotel in Pyongyang, where they waited. Lee said she saw North Koreans wearing suits and earpieces walking the halls, so she knew someone from outside North Korea was in the building. Finally, the women were taken to another room.

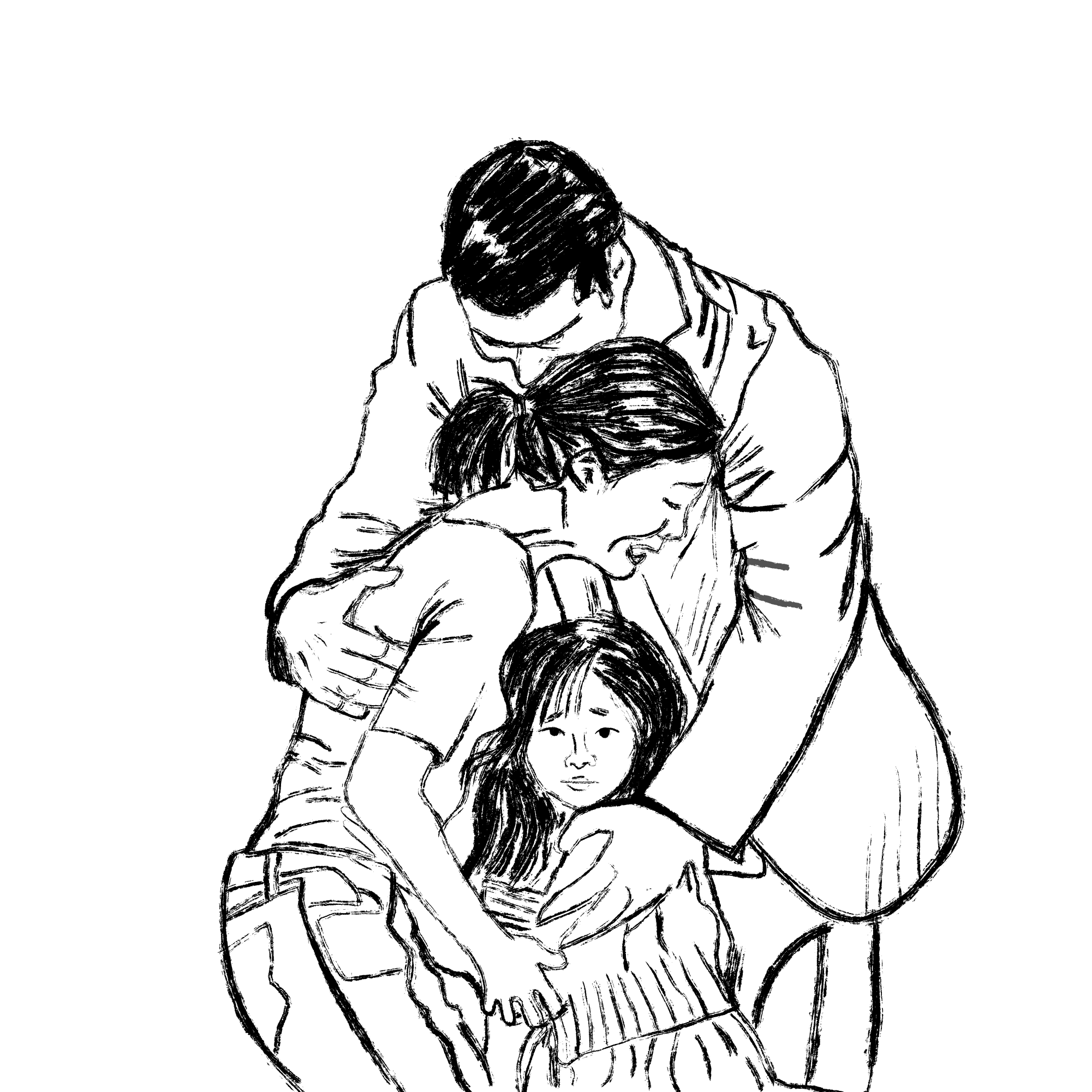

“A door was opened,” Lee said. “There was [former] President Bill Clinton standing on the other side and he opened his arms for us. There was a huge window behind him so you could see a halo around his gray hair. We both ran to him. He gave us a hug and asked us if we were okay.”

Clinton asked another question: “Are you able to fly?”

Nowadays, more and more humanitarian organizations are attempting to organize escape trips for North Koreans so they don’t have to make the treacherous journey with a paid broker. LiNK is a nonprofit that uses 3,000 mile-long routes to bring North Korean defectors into the safety of South Korea or other southeastern Asian countries.

There are more ways that organizations aid North Korean refugees. The Korea Hana Foundation and People for Successful COrean REunification help them settle in South Korea by providing housing funds, medical expenses, employment, and youth education. Hanawon is a South Korean government resettlement facility for North Korean defectors that offers a 12-week program to teach essential skills for social assimilation.

“My great hope is that the North Korean people will one day be able to determine their own destiny,” Ling said. She will continue to share the stories of North Korean defectors, even though Current TV’s documentary was never aired.

After meeting the women, Clinton explained to Ling and Lee that he was attending a critical three-hour meeting and dinner with North Korean supreme leader Kim Jong-il to secure their release. His secret visit had been planned for months before.

Ultimately, Clinton — an international celebrity — was sent to negotiate the women’s release because North Korea had chosen him. Multiple other government officials, including former Vice President Al Gore and New Mexico Gov. Bill Richardson, who had previous experience bringing Americans home from North Korea, had been denied by the North Korean government.

The next morning, Ling and Lee were woken at 4 a.m. By 6 a.m., they were pardoned by North Korean officials, and soon after that they boarded a private plane, donated by Hollywood producer and Clinton friend Steve Bing’s company Shangri-La Entertainment.

“It was so surreal,” Lee said. “You’re detained for 140 days and the next day, you’re in a private jet with a former president. I called my husband and he told me, call me when you’re in the air. I couldn’t open my champagne bottle until I was for sure in free air, knowing that soon I’d be with my family.”

The women and former president landed in Los Angeles on August 5, 2009. Their friends and families, government officials (including Al Gore), and members of the press were waiting for them.

The first people Ling and Lee embraced were their husbands. Lee remembered her daughter Hana not immediately running in for a hug.

“I asked Hana, ‘do you remember me?’” she said. “It’s mom.”

Lee lost 17 pounds in North Korea, so she understood why her four-year-old wouldn’t be able to remember her.

“She was very confused,” Lee continued. “I asked her, ‘can you give me a hug?’ She slowly walked over and gave me a hug. I remember that moment and how much it meant to me. Nothing else was important.”

Ling and her sister gave speeches to explain what had happened in North Korea and to ask the public to grant them privacy while the women adjust back to life in America.

“It was hard trying to shine a light on the plight of North Korean defectors who are living such a difficult situation and then to have the spotlight shined on us. We were reporting on a story, but then we became the story,” Ling said. “It was hard to deal with cameras pointed at us, so what’s interesting and ironic is that I went into a self-imposed isolation. I didn’t really want to leave my house because I didn’t want to face any spotlight.”

Lee also tried to remove herself from the public eye, her daughter Hana Saldate said.

“We moved across the country, from LA to New York, to shift our lives so that everything could be normal,” Saldate said. “She could have gone into a more glamorous lifestyle, going to the networking, social events with all these celebrities. But she decided to have more of a normal life. And, you know, most people don’t know that.”

Ling said it was difficult to see how her detainment impacted her parents. She carried a lot of guilt for how old, weathered, and worried they looked. Nonetheless, she grew closer with them and her sister Lisa Ling, who was instrumental in organizing her release.

“My sister and I spoke two times a day before this happened,” Ling said. “Now, we probably speak five or eight times a day. I think my imprisonment only helped us become even closer. Euna and I still keep in touch, too.”

Although having to attend therapy, being physically weak, and sustaining scars on her head from the original scuffle on the Tumen river, Ling was constantly grateful for small, beautiful moments she experienced after being freed.

“There were the little things that were so important to me: taking a walk, seeing the stars at night, breathing fresh air, listening to music,” Ling said. “I try to be much more present in life. In North Korea, I would think about something that happened to me that day and I would actually express some gratitude for it. Like, ‘I feel grateful that I saw a butterfly outside my window today, even though I’m not allowed to go outside.’ Thinking about those things kept me going, and it’s something that I continue to do to this day.”

Lee said her imprisonment has not only had emotional, mental, and physical impacts on her, but also her family. Saldate recalled being confused about the whereabouts of her mother.

“My dad kept a lot of information and tried to distract me. I knew she was on a work trip but she wasn’t coming home for a really long time,” Saldate said. “Some people at school would tease me and kind of make fun of the fact that she wasn’t here and that she was in North Korea. I was not able to comprehend the whole issue.”

After returning home, Lee didn’t feel normal for around seven years, which meant she couldn’t sleep with the door closed, she’d get claustrophobic in a room with no windows, and she’d become anxious in unexpected situations. She said she noticed her unstableness affected her husband and daughter, but she continued to be more present in their lives.

“I recognized that she was my mother, but she seemed completely different, like her personality shifted,” Saldate said. “Her energy was different when she came back, and it was hard adjusting to that change.”

“I was a workaholic before. My career was very important to me,” Lee said. “After, I was forced to focus on my family, on my daughter. So I went to all the school trips as a chaperone. My schedule was around her. I’m very thankful that I was able to spend that time with her when she was younger—when she needed her mom the most.”

A year after returning from North Korea, Ling gave birth to a baby girl: Li Jefferson Clayton. “Li” is inspired by her sister’s name, Lisa, while “Jefferson” copies former President Bill Clinton’s middle name. Now, Ling has two children, who are 14 and 10 years old. She said she is open to speaking about her time in North Korea with them, but they don’t often talk about it.

“They know what happened, to some extent. But it’s not a big dinnertime conversation,” she said with a laugh.

Both Ling and Lee wrote books about their journeys. Ling co-wrote “Somewhere Inside: One Sister’s Captivity in North Korea and the Other’s Fight to Bring Her Home” with her sister and Lee wrote “The World is Bigger Now: An American Journalist’s Release From Captivity in North Korea.”

Ling said it was a special experience to write with her sister, who is her best friend.

“It’s really a book about sisterhood and the bonds of sisterhood as much as it is about my captivity,” Ling said. “It’s told from my perspective, but also my sister’s perspective, who was on the other side. It was very cathartic for me to write when I came back to kind of get it all out there, in my own words. And in some sense, I closed that book and closed that chapter in my life.”

Despite not planning to write a memoir, Lee said it ended up being cathartic.

“I shared this story with my old colleagues and friends. My friend really insisted that I should write a book so I can tell the story from my own account,” Lee said. “It was a healing process for me. Also, now, my memory may be a little bit different. But the book, at the time, was as fresh as a memory that I had.”

Fifteen years after their imprisonment in North Korea, Ling and Lee are viewing their experiences in the context of journalism and international affairs.

Lee is head of Program Acquisitions and Commissioning for Voice of America, a U.S.-international broadcaster that provides news and information in over 45 languages. She said her job is to bring the full story to her multinational audience, some of which could be in authoritarian countries, such as North Korea.

“I was thirsty for the information when I was detained,” Lee said. “I work on a documentary series called 52 Documentary and we’re doing human interest stories. I’m so thankful that I can make this series for people to see the world if they never travel, and for people to meet others with different perspectives that they will never meet otherwise.”

Ling is vice president of programs at Very Local, an app that provides local news, weather, original series, and specials. When she began working again after her imprisonment, she continued producing series and documentaries with positive and inspiring angles.

“I try to focus on stories of humanity,” she said. “It’s a tough world to navigate in terms of journalism. Because there is so much misinformation out there, it is even more important that we have journalists who are out there pounding the pavement to shine a light on stories that need to be told. But, I now have a family, so I really look to the next generation to be able to lead that charge.”

Currently, Euna Lee lives with her husband in Washington, D.C.

Laura Ling and her family live in Mill Valley, Ca.