On the evening of March 5, my Facebook news feed was inundated with links to a YouTube video. I ignored the link, assuming that I would be sent to view the typical viral video consisting of babbling twin babies or maybe a toddler performing on the ukulele. However as the night went on, the number of posts about the video began to increase, compelling me to watch it. Much to my surprise, the video featured neither sneezing pandas nor talking cats, but instead was a 30 minute documentary created by the non-profit group Invisible Children entitled, “KONY 2012.”

For the next 30 minutes I sat at my computer watching the video, which has now been viewed over 84 million times. From the opening montage of the video to the final scene, pleading for viewers to take up the cause of making Ugandan warlord Joseph Kony famous, there was something about the video that rubbed me the wrong way. At first I couldn’t pinpoint the root of my disenchantment, however, I’ve now realized that my problem with the video has do with the video’s director, Jason Russell.

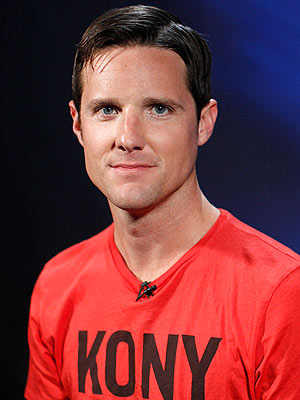

Russell, a University of Southern California film school graduate, created the video to introduce Kony and the egregious war crimes he has committed to the world. Russell and his colleagues at Invisible Children hope to make Kony famous in order to gain American military support for the warlord’s capture. While it’s true that Kony is now a household name, ironically, the video has made Russell just as famous.

Although I have a feeling that Russell has narcissistic tendencies, I can’t say for sure whether Russell wanted to become famous from making his video. I do know, however, that his rise to stardom was inevitable given the way in which he created the video. The focus of the video is on Russell’s personal story and how he came to know about Kony. Russell informs the viewer that a trip to Uganda in 2003 in which he met a former child soldier named Jacob, changed the “course of [his] life entirely.” Russell goes on to explain that he made a promise to Jacob to put a stop to Kony and the rest of the video focuses on Russell’s personal quest to fulfill this promise. The video places so much emphasis on Russell’s promise and self-given duty that the viewer is left with very few substantial and important facts. Russell spends more time talking about how he hopes to make the world a better place for his son, Gavin, than discussing the realities of being a child soldier.

The personal nature of the film is probably what attracted so many people to the Kony 2012 cause originally. Russell’s story and the appearances by his young son, surely pulled at viewers’ heartstrings. Russell made viewers believe that by purchasing a $30 “action kit”—consisting of stickers, posters, and bracelets (similar to plastic Livestrong bracelets, but this time with a classier touch)—that they would be helping capture Kony and therefore, according to Russell, “changing the course of history.” In reality, the purchase of an action kit will do little to change the world. In fact, the capture of Kony will not bring about a more peaceful world as Russell suggests throughout the video. Many people in the international world, including Ugandans themselves, have criticized Russell and his film’s oversimplification of what is in reality, a very complex situation. Many have pointed out that military action against Kony is the last thing needed, especially given the fact that Kony has been relatively inactive and it’s even unsure which African country he is currently located in. As Invisible Children and the Kony 2012 campaign have come under criticism, Jason Russell did not take a firm stand to back up the information that he presented in the video. In one interview, when asked about the criticism, Russell responded with his usual smarminess, “Haters are going to hate.”

Apparently these “haters” are what caused Russell to have a psychotic episode on March 15, in which he ran through the streets of San Diego naked and shouting obscenities. In a statement released by his wife Danica, Russell fell apart “because of how personal the film is” and that “many of the attacks against it were also very personal, and Jason took them very hard.” Although it’s sad that someone would have such a breakdown, it’s hard to feel sympathetic for Russell. He made a choice to make the film have a personal focus and he chose to take simple questions as “attacks” against himself. By making the film so personal, and having a breakdown, Russell and the Kony 2012 much of credibility it may have had. After TMZ leaked a video of a naked Russell, people created memes and parody videos for a new movement known as “Horny 2012.” Russell, replaced Whitney Houston, as the celebrity of the hour, on shows, such as “Entertainment Tonight” and the “Insider.” And those “social activists” who had purchased action kits, forgot about Uganda, instead devoting their time to finding out more about Russell’s placement in a mental hospital.

Humanitarian work is supposed to be selfless. With any non-profit effort, the main goal should be to give the voice to the voiceless. Russell and the Kony 2012 movement have redefined what it means to be a social activist, and unfortunately, not for the better.

Anonymous ♦ Apr 19, 2012 at 11:38 pm

We are not “haters” we want peace: http://uncoverthenight.tumblr.com/