Don’t look down. Whether sprawled on the court or the turf on the field, the thought is the same: if you don’t look at the knee, then there’s no swelling. You won’t have heard the infamous pop all athletes dread. You’ll be able to stand on your own and run. Your season won’t be over. But reality crashes in. You heard the pop and you feel the pain. You’ve torn your ACL.

“The sound is like a thousand people cracking their knuckles at the same time. It’s kinda grotesque,” senior varsity basketball player Walker Sapp said. “It hurts, but the reason people are yelling and screaming on the ground is because of the shock of feeling something inside your body pop like that.”

“On a scale of one to ten, [the pain] was like a nine,” junior and varsity basketball player Jaiana Harris said. “It was really painful. What made it worse was that I heard the pop, but I didn’t want to believe I had hurt it. I knew something was wrong, but I was in denial…I was in shock, so I didn’t cry immediately, but after thirty or forty seconds of being on the ground, I just burst out into tears.”

Dr. Jo Hannafin, the president of the American Orthopedic Society for Sports Medicine, noted, in a Lohud.com article, that the rates of Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) tears have increased over time, and the injury is becoming more common in young athletes. “With year-round sports, no one ever has the chance to rest,” she said. This theory applies to Tam athletes, as many are playing on a year-round club team in addition to playing for the school. This results in many Tam athletes not having an understanding of the term “off-season.”

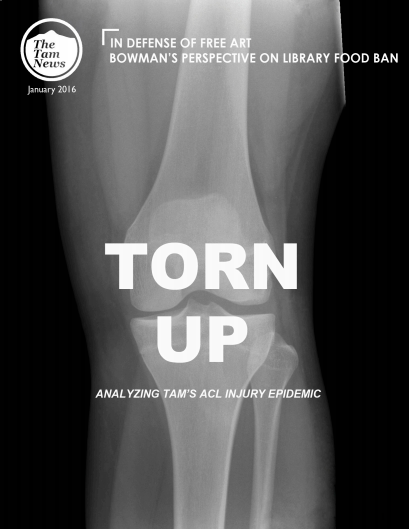

The ACL is one of two ligaments that cross in the middle of the knee, connecting the thighbone to the shinbone, helping stabilize the knee joint. ACL tears are most common in sports that involve cutting and changing direction, such as soccer, basketball, skiing, football, and lacrosse. Teenage females are six times more likely to tear their ACL than their male counterparts, according to the Mayo Clinic, because of a difference in pelvis and lower leg alignment, looser ligaments (tissues that connect bones), and the effects of estrogen on ligament properties.

Sports physician Dr. Steven Horwitz wrote that two thirds of ACL tears result from non-contact situations, such as a sudden change in direction, a one step deceleration, or landing a jump in an awkward position. “The girl had the soccer ball in front of me and I stepped to her, going in with both feet, just like any person would, and the knee popped,” said junior and varsity soccer player Addison Ball. “It wasn’t even a crazy tackle, it was just like jumping on your leg.”

According to the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons, a torn ACL doesn’t need surgery if the subject does light work or lives a sedentary lifestyle. However, athletes who wish to return to sports will require surgery. In surgery, the ACL is replaced by a substitute graft made of tendon from a hamstring, quadricep, or patellar tendon of either the athlete’s body or that of a cadaver.

“They took a part of my hamstring and used part of a dead person’s because I didn’t have enough in my hamstring [to make the graft] and [then they] pieced [the ACL] back together, totally reconstructing my knee,” freshman skier Madeline Bell said.

An ACL tear not only takes athletes out of their sports, but also greatly impacts all other aspects of their lives. They endure a four-hour surgery, followed by six to 14 months of recovery, depending on the size of the tear. The athlete is on crutches for up to four months of this rehabilitation process. This can make something as rudimentary as navigating Tam’s stair-riddled campus a strenuous task.

The first step of rehabilitation is to simply regain the ability to walk. “Immediately after their surgery, the main focus is on continuing to reduce swelling and getting the knee’s full range of motion back,” Tam athletic trainer Aubrey Yanda said. “As they progress they’re adding different weight training, they’re increasing the amount of range of motion they have, until finally they regain all their strength and all their motion.”

“For a month right after my surgery I was working on getting my motion back, because I couldn’t bend or straighten my knee and you can’t walk until you’re able to bend and straighten your knee all the way,” Harris said.

Doing all of the basic rehabilitation necessary to regain their strength and full range of motion is just the beginning. For athletes who want to return to competitive play, sport-specific rehabilitation is the next step to full recovery. This rehabilitation process integrates dynamic movements such as running, pivoting, and jumping back into the athlete’s lifestyle.

“You have to re-teach yourself to do everything on the field because what happens when you get surgery is it completely rips apart the basic movement in your leg, so your leg as well as your brain need to re-learn how to do basic things, like walking and running,” Ball said.

Getting through the physical trauma and rehabilitation aren’t the only challenges faced by student athletes who’ve suffered an ACL tear. The injury also has psychological implications. “It messed me up mentally more than it did physically,” Harris said. “I woke up every day knowing that I wouldn’t be able to play basketball for the year. I told myself I wasn’t going to play anymore the first like couple weeks after the surgery because it was hard: I didn’t know how to walk—I couldn’t walk. It just felt like I never was going to be able to play again, so I told myself I wasn’t going to play again.”

Coaches and training staff often notice this detrimental impact on the athlete’s mentality and sense of self. “Mentally, these athletes go through every stage of mourning. There’s denial, grief, bargaining, all of that they go through,” Yanda said. “It’s really hard to see someone who’s worked this hard, who’s put so much time in, and then you see an injury like this. It’s something you have to be mentally tough to go through.”

Tam girls’ varsity soccer coach Shane Kennedy echoed Yanda. “It’s really hard, I think that the physical component is probably the easier of the two,” Kennedy said. “Kids are so athletic and so active, and [their] bodies are so used to that activity, that kind of sets up the other parts of their lives, it’s calming for [them]. [They] kind of have exercise to work out anxiety, academics or whatever. That’s all gone, the camaraderie of team is gone, the feeling of accomplishment maybe is gone a little bit. I think that’s as big a piece as the physical component.”

FIFA’s Medical Assessment and Research Center (F-MARC) has found that the risk of sustaining an ACL injury can be reduced through specific training. To address this F-MARC has developed FIFA 11+, an injury prevention warm-up program. The program is to be implemented at the beginning of a training session and is composed of 15 exercises with emphasis on body control, straight leg alignment, knee-over-toe position, and soft landings.

According to the program’s informational brochure, “It has been shown that youth football teams using the FIFA 11+ as a standard warm-up had a significantly lower risk of injury than teams that warmed up as usual. Female and male teams that performed the FIFA 11+ regularly at least twice a week had 30-50 percent fewer training and match injuries.”

Dr. Noel C. Barengo of the University of Bogotá and Dr. Oluwatoyosi B. A. Owoeye of the University of Lagos both did studies testing the effectiveness of FIFA 11+. Each study confirmed that teams that incorporated the program into training sessions experienced a decrease in injuries while the players’ motor skills also improved. “Evidence of these improvements in performance are important in ‘marketing’ the program to coaches, players, and clubs since the injury may be seen as a random event,” Barengo’s study stated.

Owoeye’s study also supports an implementation of FIFA 11+ into youth athletics, concluding, “A country-wide campaign and implementation of the FIFA 11+ injury prevention programme may be pursued by youth football administrators and federations across Nigeria and regions of Africa respectively in order to help minimize the risk of injury among players. The world governing body for football (FIFA) should consider supporting federations and local administrators in achieving this.”

Some Tam teams are taking steps to prevent ACL tears in their athletes through a redesign of their team warm-ups using the FIFA 11+ program. Though the program was designed for soccer players, it can be modified for athletes of different sports.

“Varsity boys basketball did a preseason injury prevention program using FIFA 11+,” Yanda said. “They did six weeks where we did a training session every Thursday, for about thirty to thirty-five minutes. I’ve done some of the prevention strategies with individual members of girls’ basketball and girls’ soccer, so everybody’s kind of getting their feet in it.”

Boys’ varsity basketball head coach Tim Morgan thought the program helped his athletes. “I think the pre-season training went well,” Morgan said. “I think next year we’ll do it twice a week. This year it was about once a week. I think the more we can, the more we have those types of workouts, I think it will benefit everyone.”

FIFA 11+ has only been implemented team-wide in the boys’ varsity basketball program. Along with Morgan, Kennedy is also behind integrating an injury program into pre-season and regular season training, but recognizes finding time to do so is a challenge.

“It is difficult to do pre-season injury prevention programs since many players are with club teams during that time,” Kennedy said. “During the season it’s difficult because of the limited amount of practice time. If we could find a way to make more time for injury prevention training, I would definitely be behind it.”

Athletes also support the integration of the program into their training regimen. “ACL prevention definitely should be done [at Tam]…the teams I’ve been on haven’t done much of it,” sophomore varsity basketball player Alexis Travers said. “Having torn my ACL, I’m behind [ACL injury prevention] even more. We wouldn’t lose great players during the middle of the season for some stupid twist of their leg that could have been prevented with some early-season stuff….If we could just prevent those things, prevent the kind of physical and mental pain this injury causes people, it would be so much better.”

Ball echoed the same sentiment. “I don’t think the current ACL prevention program at this school is enough,” she said. “I really think that it should be a standard at this school to have at least at the beginning of training sessions an ACL warm-up, because [ACL tears] have affected so many people at this school, and it’s going to continue affecting people, if we don’t strengthen in that regard. I never thought that I was going to tear one, not in a million years. I think that this school should be supporting injury prevention in every sport.”

Many members of the Tam community are student athletes. For them an ACL tear derails their season and takes focus away from their everyday lives. ACL injuries can affect an athlete for over a year and any means of prevention that can potentially reduce the detrimental physical and mental effects on their lives should be utilized.

“There are prevention strategies such as FIFA 11+ out there that don’t cost a lot of money and it just takes a little bit of time to do them,” Yanda said.

“They’re shown to work to prevent injuries, and even if the entire team has to do it to prevent one injury, it saves six to nine months of rehab time and it allows players to stay on the field and do what they want to do. I think that there’s always going to be injury. We can’t stop that, but if we know what we can do to help try to prevent it, that’s really the direction we need to go.”