The Reality of Consumerism

Dec 13, 2021

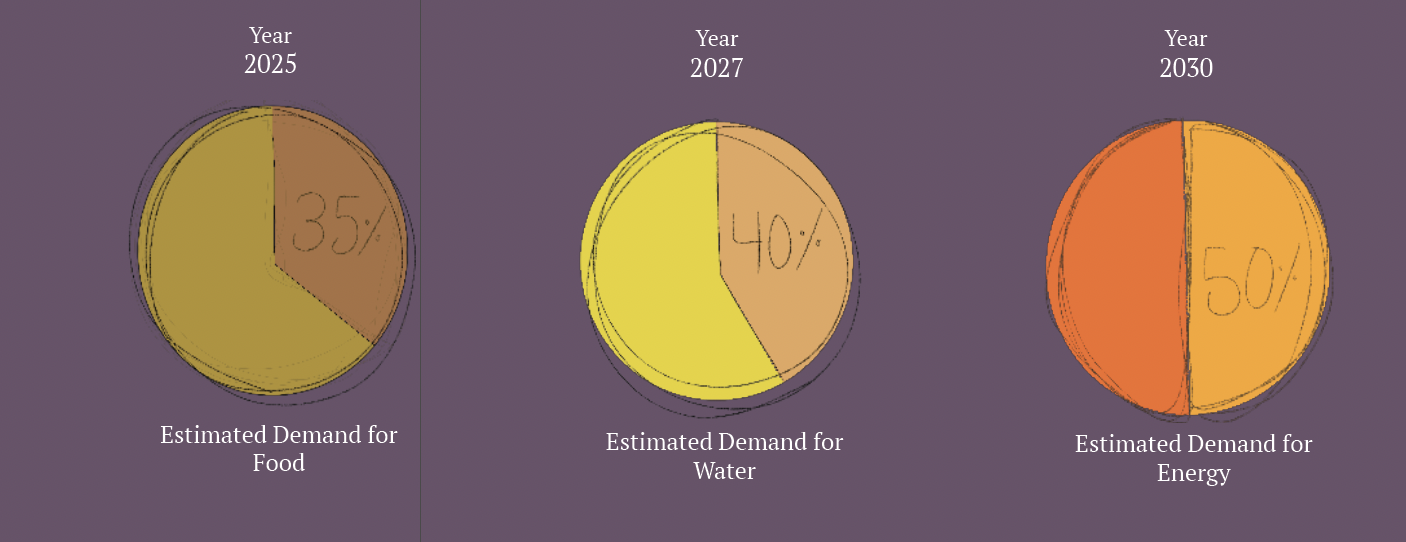

According to the European Commission, the middle-class is projected to reach 5.3 billion people worldwide by 2030, with the potential to drive economic development across the globe. But with more than half the world’s population soon to be a part of what’s also known as the “consumer-class,” characterized by the ability to buy goods beyond what satisfies basic needs, consumer behavior and consumption patterns will undergo immense growth. The European Commission estimates that the demand for food, water, and energy will respectively increase by approximately 35 percent, 40 percent, and 50 percent by the end of this decade.

“Rising consumption has helped meet basic needs and create jobs,” Christopher Flavin, president of Worldwatch Institute (WI) said in a statement. WI is an independent research organization devoted to environmental research.

“But as we enter a new century, this unprecedented consumer appetite is undermining the natural systems we all depend on, and making it even harder for the world’s poor to meet their basic needs,” Flavin said.

Consumer Responsibility

The ties between consumerism and climate change can be overlooked to maintain the comfortable lifestyles that thoughtless purchasing provides, making it valuable to be aware of the larger-scale impact that major companies like Amazon have on the environment. However, research from the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NUST) has shown that consumers are responsible for more than 60 percent of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions, and up to 80 percent of the globe’s water use. In addition, the university’s analysis, completed in 2016, revealed that consumers are directly responsible for 20 percent of all carbon impacts, four-fifths of which are known as secondary impacts. Unlike direct impacts, such as the fuel burned from driving a car, secondary impact refers to the actual production of the products that are bought and impact the environment.

Something similar to secondary impact is seen in the case of the livestock industry, a major example of wasteful consumer behavior. In general, much of the water use on our planet is seen in the production of products you buy.

Agricultural Industry

Research from NUST explores how the farming of meat displays a massive amount of water usage. Their team has found that beef, for instance, takes an average of 6,600 gallons of water to produce eight ounces of meat. This is because cows are relatively inefficient when converting grains, which require water to grow, into the meat that we eat. In addition, 16 percent of the world’s methane, a destructive greenhouse gas, is produced by livestock due to the animal’s belching and flatulence. NUST also has examined how large amounts of manure from factory farms becomes toxic waste rather than a fertilizer. The runoff of which is a contamination threat to nearby streams, bays, and estuaries.

“[Your diet] has a major impact [on the environment] and is also something that we have a lot of control over, so that’s good news. The problem is ours but the solution is also ours. So I would say that with the growing of crops to feed to animals to then eat the animals, couldn’t we just eat the crops? Even just a gradual shift away from meat every day, every meal. Meatless Monday you know, that’s a 14 percent cut immediately,” AP Environmental Science and Physics teacher John Ginsburg said about the way someone’s diet affects their carbon footprint.

Adding to the discussion on food imports, Living Earth and AP Environmental Science teacher Quinlan Brow explained the impact of agricultural globalism concerning consumerism. “If we’re thinking about eliminating a lot of the emissions from food exporting and kind of just traveling food all over the place, it would be much more sustainable to have only local networks that you’re dependent on. But because we can [import food], we do. And it’s not really considering the negative externalities of that,” Brow said.

Fast Fashion

The idea of “because we can, we do” plays a major role in consumerism culture. For instance, the affordability of fast fashion clothing paired with new trends influences consumers to continue purchasing from unsustainable brands such as Shien, H&M, and Urban Outfitters. The fashion industry itself consumes one-tenth of all the water used industrially in order to run factories and clean products, according to research from Princeton University. The same study from Princeton University shows that this is evident in that it takes nearly 800 gallons of water being used to produce one cotton shirt and around 2,000 gallons to make a typical pair of jeans. And research from the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) reveals that approximately 20 percent of worldwide wastewater can be attributed to this process. Oftentimes, the wastewater produced is extremely toxic and unable to be treated for continued use.

In addition, many overseas factories are in countries without strict environmental regulations, allowing for untreated water to enter and pollute the ocean. UNEP has also found that the fashion industry produces upwards of 8 percent of global carbon emissions.

Moreover, UNEP states that the quantity of clothing our society consumes globally has skyrocketed over the past few decades. The economic benefits of this are heavily outweighed by the increase in cheap clothing that finds itself in landfills.

One fate thrown-out clothing faces is incineration. Princeton University research explains that 57 percent of all discarded clothing ends up in landfills. When the landfill then exceeds its maximum size, the trash is moved along to be incinerated. The Conservation Law Foundation (CLF) explains what this process entails: “Incinerator companies have done a great job green-washing their true impacts on communities by implying that so-called ‘waste-to-incineration’ facilities are good neighbors offering a safe process that eliminates waste, allows for robust recycling programs, and generates renewable energy. Nothing could be further from the truth. The reality is burning waste harms the health, environment, and economy of many communities. The perceived benefits simply aren’t worth the risk,” CLF stated in 2018.

Clothing Decay

Another impact from clothing in landfills is when the organic materials such as cotton, flax, wool, or silk begin to decay. “Something that I think is a bit surprising is the number of emissions that come from clothing,” Ginsburg said. “And clothing sitting in landfills, which makes sense when you think about it. Cotton is decaying, it’s decaying in the absence of oxygen, which means it’s producing methane, methane being a greenhouse gas that’s 20 times worse than CO2. And I think consumerism feeds into that because people have a sense that all they want is the newest fashion and what did they do with their old clothes? Sometimes they donate, but sometimes they just toss them in the landfill.”

To add, Planet Aid explains that this process is called anaerobic digestion and causes landfills to be one of the biggest contributors to atmospheric methane. But beyond the issue of methane, clothing in landfills can also contaminate nearby groundwater and soils through the buildup of dyes and chemicals used to make clothing. So it’s not just the production of fast fashion where wasteful resource usage is seen, but also the afterlife of overproduced clothing.

Sustainable Fashion

Environmental Science and Physics in the Universe teacher Jessica Watts offered a more optimistic view on the topic of fashion. “I’ve been teaching for 10 years now and one thing that does make me excited is that I’ve seen a bit of a shift in that it’s more popular to go thrift shopping and to try and consume less. So that makes me really excited and I know at least when I was in high school, the cool thing was having ‘that bag,’ or ‘that necklace,’ or ‘that type of clothing.’ I mean there’s definitely always going to be some of that, it’s very deeply embedded in our culture. But it’s really cool to see that that’s starting to shift because your generation has been seeing the ramifications of so much of industrialism,” Watts said.

Thrift shopping, or buying second-hand instead of brand new clothing, reduces waste by giving a new life to something that would’ve otherwise gone to a landfill. Thrift stores also often retail older goods that are comparatively higher quality to fast fashion, causing purchases to last longer. But like fast fashion, shopping second-hand often offers more affordable prices without the catch of the harm production impacts have on our environment falling on the consumer.

Another alternative to buying new clothing is shopping from websites or apps, such as DePop or Poshmark, where anyone can re-sell their used clothing to other users. Sophomore Lani Tabuya and junior Jules Dockstader spoke on their experiences with the DePop, an app popular with Tam students. “I’ve used both DePop and other second hand clothing apps or websites,” Dockstader said. “They’re easier to use and somewhat, I feel like you can trust [them] a little more. They tend to have more honest reviews and it’s cool in a way since someone else has worn or made those things you buy,” Tabuya said. “It’s been easier to find clothes in my style because I can search for specific items and sizes. In a lot of cases, it’s cheaper than buying new, and I don’t feel bad about my item consumption because the item was already bought originally.”

Consumerism at Tam

As Watts mentioned, this generation, and current Tam High students, have been displaying a more acute awareness of the connection between consumerism and climate change. Ginsburg expanded on this. “I would say on the grand-scale of students in the U.S., [Tam students are] doing pretty well. I think there’s an interesting balance because in our community here, there’s a lot of consuming. Y’know we’re living in a very affluent area, there’s a lot of cars purchased, there’s big houses that are probably bigger than they need to be, and there’s certainly in a fashion sense, a lot of very fashionable choices being made and a lot of fashion purchases. I think all of it could be scaled back a little bit. But I also think that Tam students have a good heart when it comes to environmentalism and that they understand that there are difficult choices to be made but they’re willing to make a lot of those choices,” Ginsburg said.

Furthermore, all three teachers agreed that consumerism culture impacts the way high schoolers live their lives. Acknowledging that, they offered insight into what teenagers can do to be a more eco-conscious consumer.

“I think just stopping and asking yourself what the impact of your decisions are,” Brow said. “So actually being more metacognitive about the cost and benefits of your decisions, about what you buy at the store, where you go on vacation, what kind of things you do. Like actually being considerate of where it came from or how it got to you, things like that … I think that taking the time to stop and think also not just about where it comes from, but do I actually need this in my life? Is one thing that I think can stop rampant consumerism. There will still be consumerism, but I don’t think it will be as gnarly if people actually took a second to stop and think about it.”

“Consider diet, and then also your consumption,” Watts said. “Which again seems to be like, I’m really excited for this fad of thrifting, and not over-consumption. And yeah, just kind of thinking about your daily things like turning off the light when you leave the room. But really, I think some of the biggest impacts are your consumption and then how you eat … You speak a lot with your dollar. And that’s something that you can use. Because this is a huge target group for a lot of retailers and people who are trying to sell you stuff.”

The Big Picture

But consumerism and climate change also need to be addressed on a nationwide, or even, global scale. In 2019, the United States was at least 15 percent above its emission reduction target outlined in the Paris Climate Agreement, according to CNBC. Countries committed to the Paris Climate Agreement aim to substantially reduce global greenhouse gas emissions and prevent global warming from rising above 1.5° Celsius, or 34.7° Fahrenheit. “It also aims to strengthen countries’ ability to deal with the impacts of climate change and support them in their efforts,” the European Commission’s official website states. Though former President Donald Trump withdrew the U.S. from the Paris Climate Change Agreement on Nov. 4 last year, President Joe Biden signed the U.S. back into the Paris Climate Agreement during his first day of presidency. “The window for meaningful action is now very narrow… we have no time to waste,” the chief executive of Conservation International, an environmental advocacy group, Dr. M. Sanjayan said in support of President Joe Biden’s decision.

At this rate, it’s going to take a combination of dedicated citizens and national governments to prevent further damage. “I think worldwide we need to reduce consumption and rally together to push the need for sustainable infrastructure, reducing all of these things at a national level … lobbying essentially to our political leaders to make sure that we are changing what we need to change to slow climate change,” Watts said.