San Quentin’s Mount Tamalpais College

Feb 2, 2023

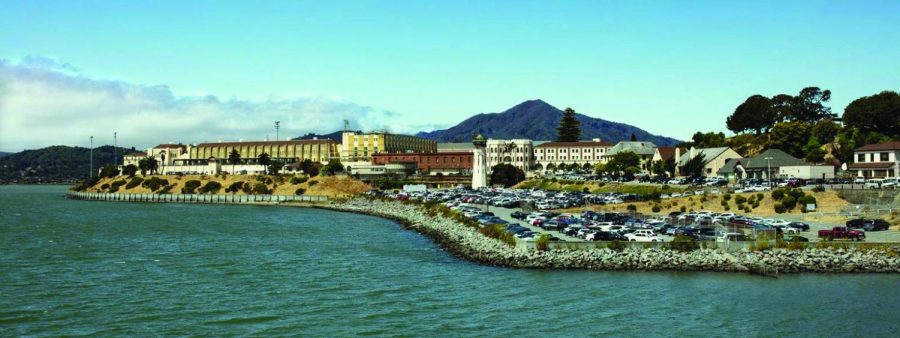

San Quentin State Prison, California’s oldest prison, opened in 1852 just miles from San Francisco, in the largely unsettled county of Marin. Now, as modernization and industrialization have transformed the prison’s surroundings in the last 150 years, a small, independent liberal arts university called Mount Tamalpais College (MTC) is working to improve the lives of its incarcerated residents.

“We, in Marin County, often see San Quentin, but we don’t think about what that means,” Tara Seekins, English teacher at Tamalpais High School and MTC volunteer, said. San Quentin is located on the highway coming off the Richmond bridge into Larkspur, and, for many Marin County residents, has become a normal part of their daily commute.

Seekins remembered a time she had driven past the prison with her five-year-old nephew, who questioned what the building was. “How do I explain to him that this is a place where people get put in cages?” she questioned at the time.

MTC has been educating incarcerated students in San Quentin for nearly 25 years. Founded in 1996 as the Prison University Project, MTC was originally an offshoot program of the nearby Patten University seeking to combat low education rates within the U.S. prison system. The program’s first Associate of Arts (AA) degree was granted three years after its founding, in 1999.

“We believe all people should have access to affordable higher education, and the opportunity to develop their human potential,” MTC’s website states. “Excellent academic preparation is vital to accessing the forms of social, political, economic, and cultural capital from which many have historically been excluded.”

For its first 20 years, MTC was the only on-site, degree-granting program in California’s prison system. It was awarded initial accreditation by the Accrediting Commission for Community and Junior Colleges in January 2022.

“There’s so much about life for people who are incarcerated that is not creative. There are a lot of places that, just by definition, freedom isn’t in [their] life,” Seekins said.

Seekins has been teaching, tutoring, and volunteering for MTC since 2009, when she was attending graduate school at University of California, Berkeley.

“But in a classroom? Students really are free; [they have] freedom of expression, freedom to defend a position with a text, freedom to explore world views, literature or art, or political theory. [Education] is an opportunity to transcend that boundary.”

Following the 1994 passage of the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act, which banned prisoners from receiving federal student aid Pell Grants, higher education within the U.S. prison system dried up. According to MTC’s website, around 350 programs around the nation shut down as a result. What followed, MTC said, was “a crisis.”

Now, MTC offers around 60 courses and has served 3,731 students over the past 25 years. It has also been recognized nationwide: in 2015, the college was awarded the National Humanities Medal by former President Barack Obama.

Enrollment in MTC is non-selective, meaning that it accepts students regardless of academic aptitude. Academic aptitude is only considered when placing students in classes: if, for example, a student doesn’t qualify for an English 101 class, they can take lower English courses offered by MTC before moving up in the program. However, students do have to qualify for the program in accordance with San Quentin’s policies, meaning that disciplinary records are taken into consideration.

“I’m so full of freedom. I’m staying in school, away from my cell, and dedicating my time to studying hard and helping my community,” MTC student Julio M. Martinez wrote in his personal essay. “I feel I have succeeded and this has made me a better man and a better friend. That is the lesson I have learned. I want to be seen as аn example in my Hispanic community.”

“Many people were incarcerated [at San Quentin] because they were participating in underground economies, because they didn’t have access to mainstream economy because of opportunity gaps, because of structural racism,” Seekins said. “And so [MTC] is kind of an interesting bridge, and that’s one of the reasons why it’s controversial, too. Because some people say ‘Why can’t my kids get free college, why should they get free college, when they’ve committed crimes?’ And there is that pushback and we just have to understand that.”

Because MTC was recently awarded initial accreditation, the AA degree students earn is transferable to a four-year college or university just as a degree earned at the College of Marin or the City College of San Francisco would be. If a student qualifies for parole and wants to seek out a higher education, they could enroll at a California State University or a UC as a junior.

“I think that not sensationalizing [MTC] is really important,” Seekins said, when asked about MTC’s humanitarian aspects. “Really, it’s just a college. That’s the idea.”

Although it isn’t charity, MTC’s educational work is a vital part of the rehabilitation process. A 2016 report by the Research and Development (RAND) Corporation, an acclaimed research nonprofit, found that inmates that participate in any educational programs while in prison are 43 percent less likely to be reincarcerated.

“We [the educators] don’t really do it for the admiration,” Seekins said. “We think it’s going to make the world better. To make people’s lives better.”

Just like teaching any other level of education, MTC’s end goal is fundamentally to provide students the tools they need to better their lives through higher education. To Seekins, these students just happen to be incarcerated people.

“The name of [Mount Tamalpais College] is intentional,” Seekins pointed out. MTC changed its name from the Prison University Project to Mount Tamalpais College in 2020. “They wanted to focus more on higher education and less on the fact that students are incarcerated.”

But the pursuit of higher education hasn’t been easy for the students at San Quentin. When the COVID pandemic hit, the prison shut down classes completely to prevent COVID transmissions.

“During the pandemic, everything closed, and the prison was locked in,” Seekins said. “The students weren’t able to get out very much at all. They were on their cells for most of the pandemic.”

In the summer of 2020, over 2,600 inmates and staff were infected with COVID-19 in what became one of the worst outbreaks in the country. The outbreak started when the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitations (CDCR) transferred 121 inmates into San Quentin from the California Institution for Men (which had the highest infection rate in the state), without testing or quarantine procedures. Twenty-nine people, both staff and inmates, died as a result of the outbreak.

“The students are very traumatized by that experience,” Seekins said. “A lot of students wanted to talk about that after classes, and a lot of them were writing about it in their essays … it was a very challenging experience.”

On Nov. 16, 2021, Marin County Superior Court Judge Geoffrey Howard ruled that the CDCR had inflicted cruel and unusual punishment on San Quentin inmates.

In-person classes resumed at San Quentin around fall 2021. Now, after COVID, Mount Tamalpais College is continuing to expand the movement for education within the U.S.’s booming prison system.

“There is an aspect of this work where —it is a college, but it’s a college operating in an extremely violent, absurd system [that exists] because we haven’t found a better solution,” Seekins said. “That’s the challenge. That’s what future generations are going to have to keep pushing toward: a more just way to have a peaceful society.”