Bolinas Under Siege: Another Chapter in Marin’s Housing Crisis

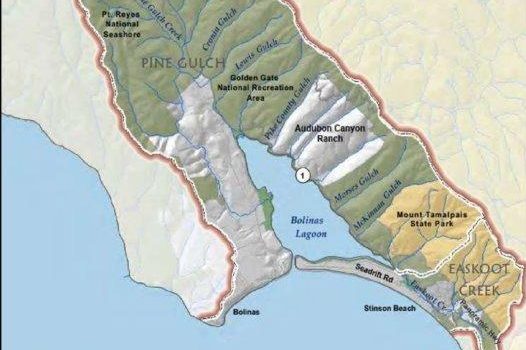

Courtesy of the Marin County Public Works Department

Map of Bolinas Watershed

May 30, 2023

It would be an understatement to label the unincorporated Marin Country community of Bolinas, Calif., a “reclusive environment.” With a population of a little under 1,500 residents, per the 2020 census, the coastal town is located about 13 miles northwest of San Francisco as the crow flies. It’s 27 miles driving through unmarked State Route 1 with the signs leading any non-local to the town having been taken down by residents. Any road sign that points to Bolinas is soon taken down upon its posting, a practice of locals that brought Marin County officials to offer a ballot measure of which voters indicated a preference for no more signage, cementing the town’s preference to remain hidden.

Bolinas is the oldest town in Coastal Marin, originally home to the Coastal Miwok tribe. The first non-Native settlers were Spanish-Californians on the Mexican Land Grant and defined the boundary that included Stinson Beach and Bolinas into a single town until 1916.

The California Gold Rush of 1849, in which gold seekers flocked to Northern California led to a population influx in the town. The geographical proximity and easy access of the Bolinas Lagoon attracted loggers to the surrounding forests along with others who discovered the resources for lumber and food of the region.

The ancient redwood forests have since become grasslands as schooner traffic due to the early commerce routes of West Marin caused the town to grow around Wharf Road, essentially the downtown hub of Bolinas as of today. Schooner captains viewed Bolinas’s fertile landscape as an opportunity for ranches and farms that define the town, its economy and community, and that of the greater area.

The local production of high quality and, oftentimes, organic produce as well as other food from ranches and organic farms began in the mid-1800’s and continues today as the unmarked route to downtown Bolinas is marked with roadside farm stands and locally produced products as well as stores featuring fresh, local produce.

These organic farms have gained international recognition for the isolated town as models of sustainability and variety, from organic vegetables and fruit, crab and fish, bread and eggs, and high quality desserts and cheeses.

Notably, the counterculture of the 1960s and 1970s was pivotal to the development of Bolinas culture, as activists and artists who made up much of the towns population at the time (both on the Lagoon and surrounding area) protected it from a massive infrastructure plan that proposed numerous changes including a four-lane freeway and luxury marina.

In 1971, these residents also protested in the wake of an oil spill that attracted another influx of counterculture young people. Many of these people stayed in Bolinas, purchased homes, and became more involved in the local community as volunteer members of school boards, the local water board, and numerous nonprofits that secured the eclectic, creative, and passionate future of the area today.

These residents and the generations that followed have fought in numerous controversies with real estate developers and county politicians as they have remained committed to a community devoted to environmental preservation and individualism.

However, Bolinas is not as idealistic as it appears. It is plagued by disparities between income and the housing market. According to U.S. Census data, the median household income in Bolinas is around $86,000, while the median home cost about $2,000,000. An estimate that Smith-Marchi, who continues to visit her father in her childhood home in Bolinas, has witnessed the development of in her trips back to California.

Comparatively, residents of Mill Valley make on average $71,000 more per year, in a place with a similar median home cost.

Home prices in Bolinas sell on average for around 22.5 times the median Bolinas household income. In Mill Valley, a house costs only 12.7 times the median income. Bolinas’s housing market has taken off, with homes appreciating by 94.1 percent in the past 10 years. As the Bolinas housing market soars, the average income cannot keep up.

As a result, many residents are priced out of the community, and forced to leave. Bolinas resident, Michael Pinkman has experienced this first hand, seeing friends, families, and vital community members leaving due to the cost of living.

“Lot of great folks had to leave, it just became too expensive to live here. There isn’t enough affordable housing to meet the demand,” Pinkman said.

To make matters worse, vital properties are being rented out as short term vacation rentals. As vacation homes can be rented out for exuberant prices, they prove to be more profitable than long term rentals.

Therefore, landlords have no incentive to rent out their homes normally, and instead rent the house online on sites like Airbnb and Vrbo. Vacation rentals do have their positives, as they provide tourism to Bolinas, helping to sustain the economy.

A larger issue the community faces is the prevalence of second and third homes. Local teen, Logan Berry has noticed the prevalence of vacation homes, saying “Bolinas is so beautiful, people want to come and stay here. They’ll pay a lot of money, so people rent out their houses to the vacationers.”

However, short-term rentals aren’t the only issue residents are facing. A much larger, and even stranger issue is the issue of vacant homes in Bolinas.

Berry describes the issue, saying “There’s a lot of AirBnBs but I think there are also a lot of second and third homes,” Bolinas resident Logan Berry adds. “The owners have so much money that they don’t even need to AirBnb it, the houses just stay empty.” U.S. Census data reports that 37 percent of Bolinas houses sit vacant despite the high numbers of residents struggling to find homes.

However, the community is fighting back against the gentrification of their beloved town. As far back as the 1980s, residents were working to preserve the affordability of Bolinas.

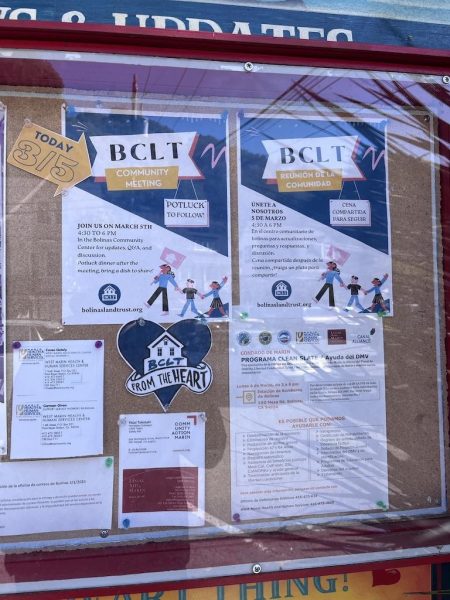

In 1982, The Bolinas Community Land Trust (BCLT) was created with the purpose of attempting to provide long-term affordable housing solutions in Bolinas.

Today, the BCLT owns five different properties in which they provide affordable housing for 31 people. They also own and operate a gas station, as well as provide the real estate for two local businesses. The work of the BCLT has been instrumental in creating low income housing in Bolinas, but their work alone has not been enough to solve the shortage.

Bolinas is an unincorporated community and falls under the jurisdiction of the Marin county government as opposed to a local authority. The Marin County Board of Supervisors members oversee their respective districts spanning Marin and deal with matters affecting the county. Supervisor Dennis Rodoni’s District 4 contains Bolinas, putting it within his oversight.

“Not a day goes by that I don’t have an inquiry about the lack of housing of Bolinas or the impacts of the lack of housing,” Supervisor Rodoni said. “It’s mostly residents who have been living in the community and their place of living has been put up for sale or changed from a long-term rental to a short-term rental.”

As the county government tries to act in Bolinas, their efforts are complicated by strict rules facing water meters. The combination of California’s drought and Bolinas’s closed watershed have led to regulations on new homes. In order to save water, there are a finite number of water meters, devices to manage a home’s water flow. As only a certain number can be in use, it is harder to build new homes in Bolinas.

“It’s a really closed watershed and they have a very limited supply,” Rodoni said. “For years now they have had a moratorium on new water meter hookups. The only way to build in Bolinas is if you purchase an existing water meter from another property.”

Action has been taken to slow down the increase of short term rentals and to figure out a long-lasting, tangible solution. The county government has worked with organizations like the aforementioned BCLT to address the crisis.

One current plan that the Board of Supervisors are implementing are incentives for building second units on Bolinas property. These second units are referred to as Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs) and work around the regulations to allow Bolinas residents to live in more affordable housing. This proposal has the favor of The Bolinas Community Public Utility District (BCPUD) President Jack Siedman.

“I would say the single most solid proposal is to create ADUs,” Siedman said, “so if you have a piece of property and you have a house on it, the county will let you build a second unit on that property and encourage you to let someone live on it.”

The situation affecting Bolinas seems dire. But the very foundations of the town can provide hope in this tough time. Bolinas is known for its resilient spirit, from protesting oil spills, to tearing down signs to protect Marin’s hidden gem, and residents don’t expect to stop now.

Former resident Carey Smith-Marchi remembers her hometown, in many ways, as an idyllic place to grow up. One that has formed much of her perspectives about the value of such small and close-knit communities that she experienced as a kid.

She has since moved from Bolinas to San Francisco, attending Urban High School, then to the southern United States for college, and finally to her current home in the Midwest she continues to live by a simple quote that comes from her Bolinas roots: “Live and let live.”