End of discussion. Period.

Sep 20, 2020

Additional reporting by Emily Stull

Menstruation is a topic kept quiet. When leaving class to go to the bathroom, people hide their tampons in a pocket, up their sleeve, or by any means necessary to conceal the real reason why they’re leaving. We live in an environment that causes women and all menstruators to feel embarrassed for having their periods. I’ll never forget the red faces I’ve encountered from teachers who, in order to go to the bathroom I had to tell them, in the least blatant way, I was having “lady troubles.”

Following my most recent article highlighting reasons why we should stop using plastic tampon applicators, I faced a profuse amount of comments about how surprised people were that The Tam News was willing to publish a piece relating to menstruation. It was “shocking” that we were “so progressive.” Hearing those comments made me wonder why a natural process performed by over half the population was so foreign and awkward— even to those who menstruate.

Part of the reason why I believe people—especially those who do not menstruate—have a hard time discussing periods is that they are not normalized.

While briefly touched upon in sex-ed and social issues, periods remain a mystery to many. Even to some women and other menstruators, periods are taboo. Worse, the actual amount high school students know about periods suggest that we may need to revisit sex-ed and start learning more about the menstrual cycle.

Through a grade-inclusive survey, it became apparent how little the subject was touched upon in sex-ed. While the basic components were there when answering questions such as “what is menstruation?” and “what is the purpose of menstruation?”, the majority of answers—including those of women—were unable to describe what the menstrual cycle was and why it occurs. Some even strayed far from the basics of biology unaware of both the purpose and process of menstruation.

“When I was doing the survey it was like ‘I kind of know’ but they didn’t really teach us that much so it does not surprise me,” junior Sophia Harkins said.

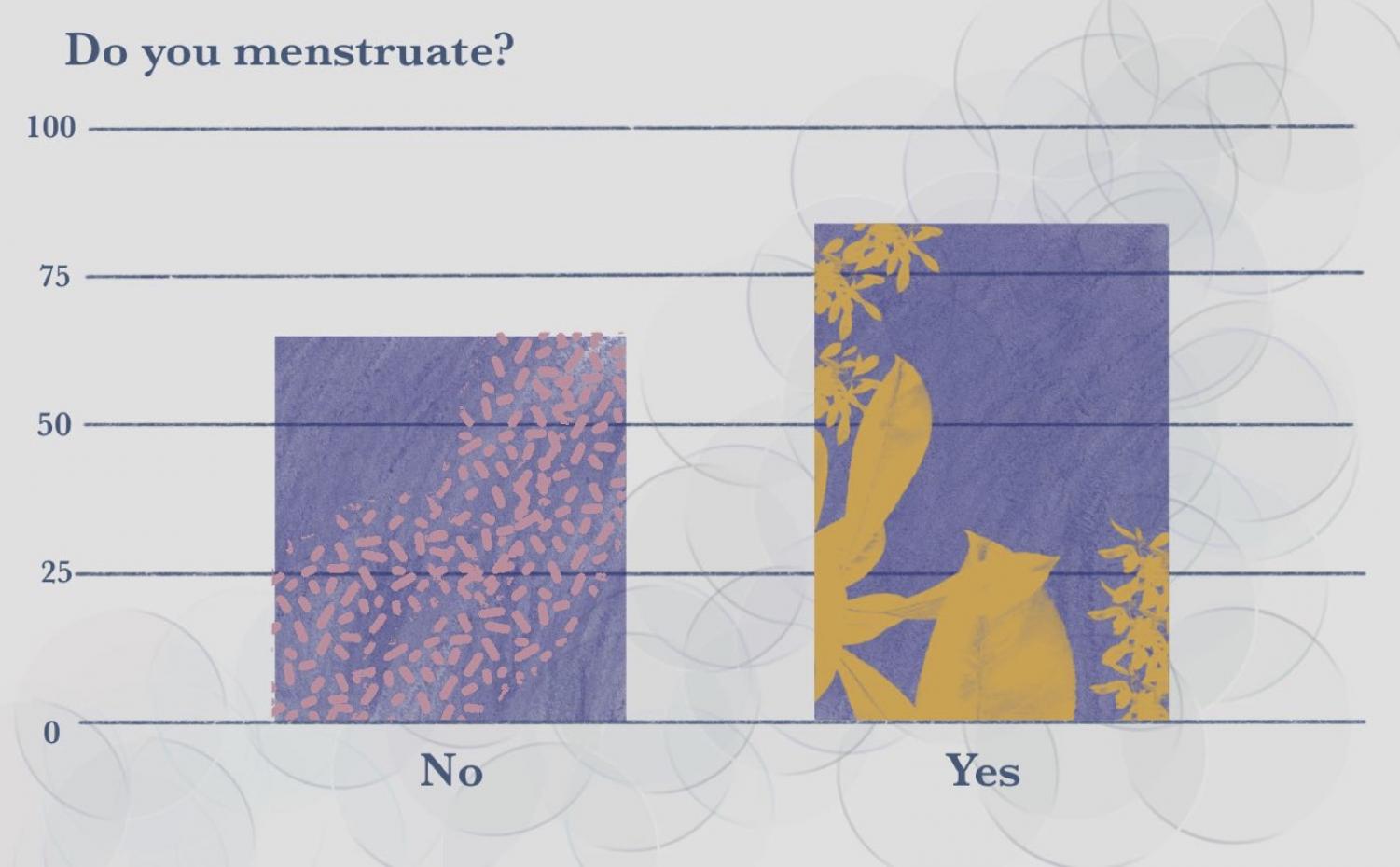

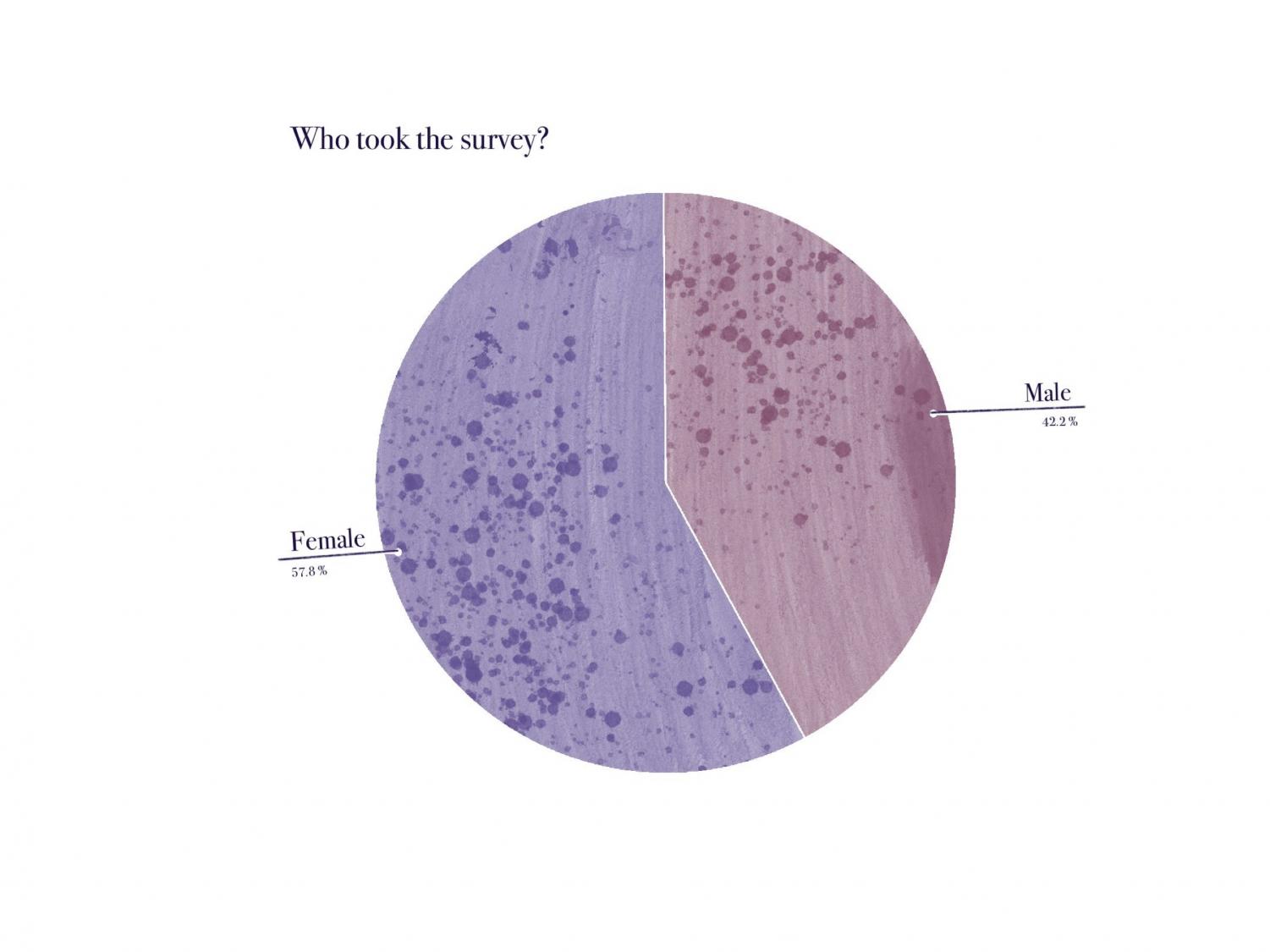

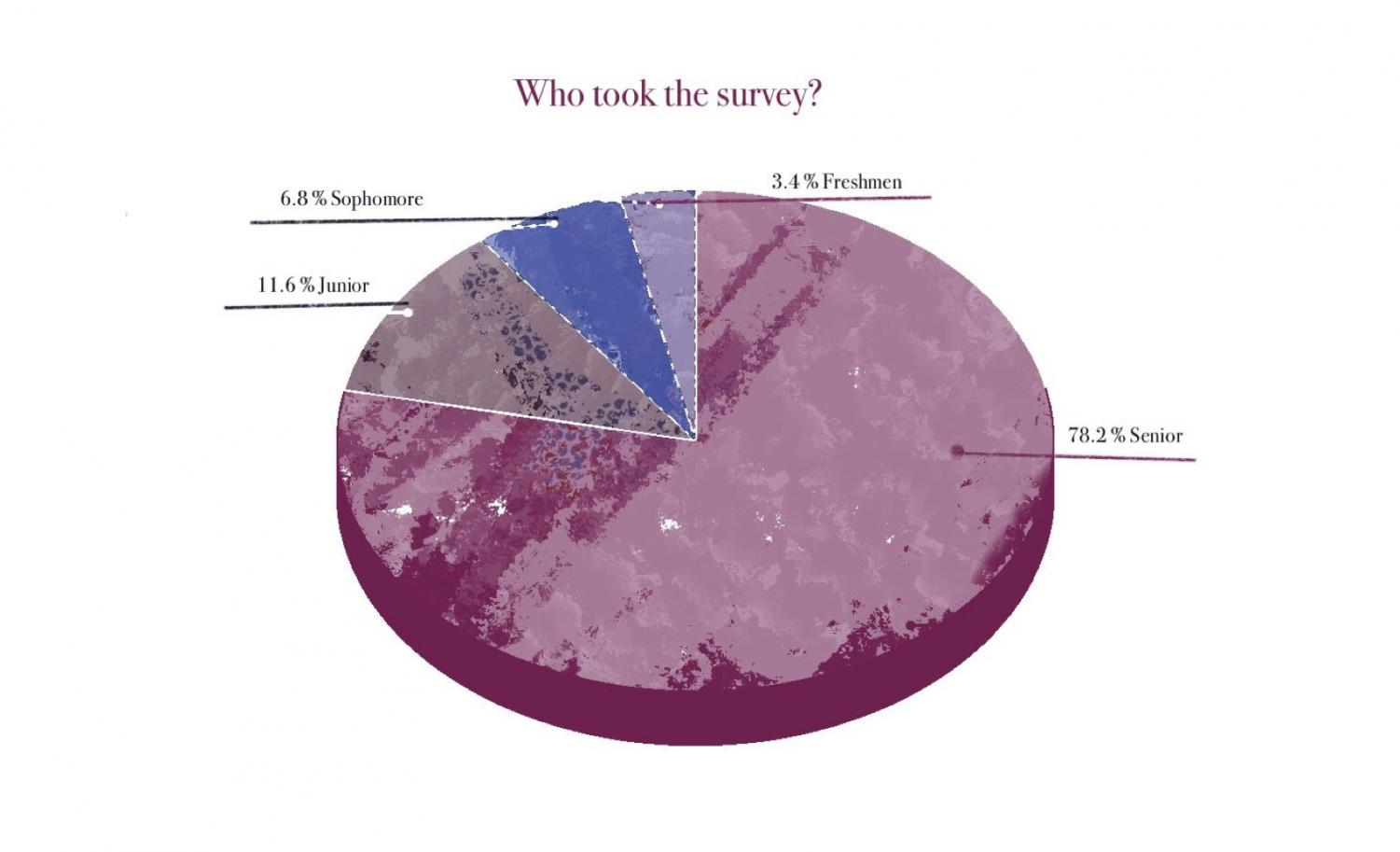

Of the 147 students who took the survey about half of the students answered with a generally correct answer. This answer was either a relative understanding of the concept or a clear understanding of the concept both with and without the inclusion of all anatomy involved with the process. Six students said they didn’t know what menstruation was, one saying “I’m not a girl so I don’t know.” Twelve students replied they didn’t know what the purpose of menstruation was answering with a range of “idk”, “no clue”, “could not tell you”, and more along those lines. Surprisingly, three students thought the purpose of menstruation was “pleasure related.” Fifty-four students, male and female, answered with “period”, “monthly blood flow”, or a similar answer, which isn’t wrong but is just another way to say menstruation. Twenty-one students very incorrectly answered what menstruation was.

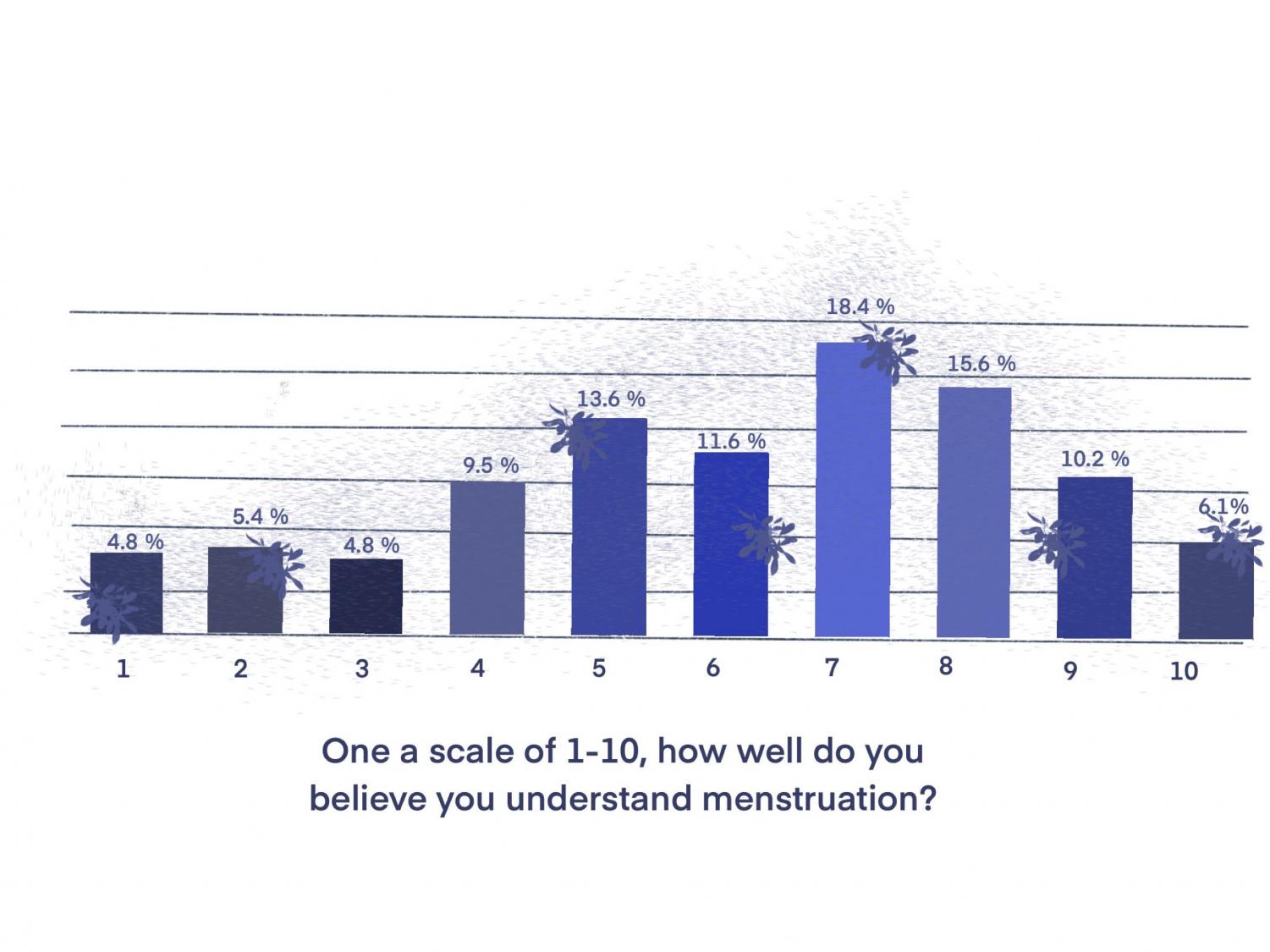

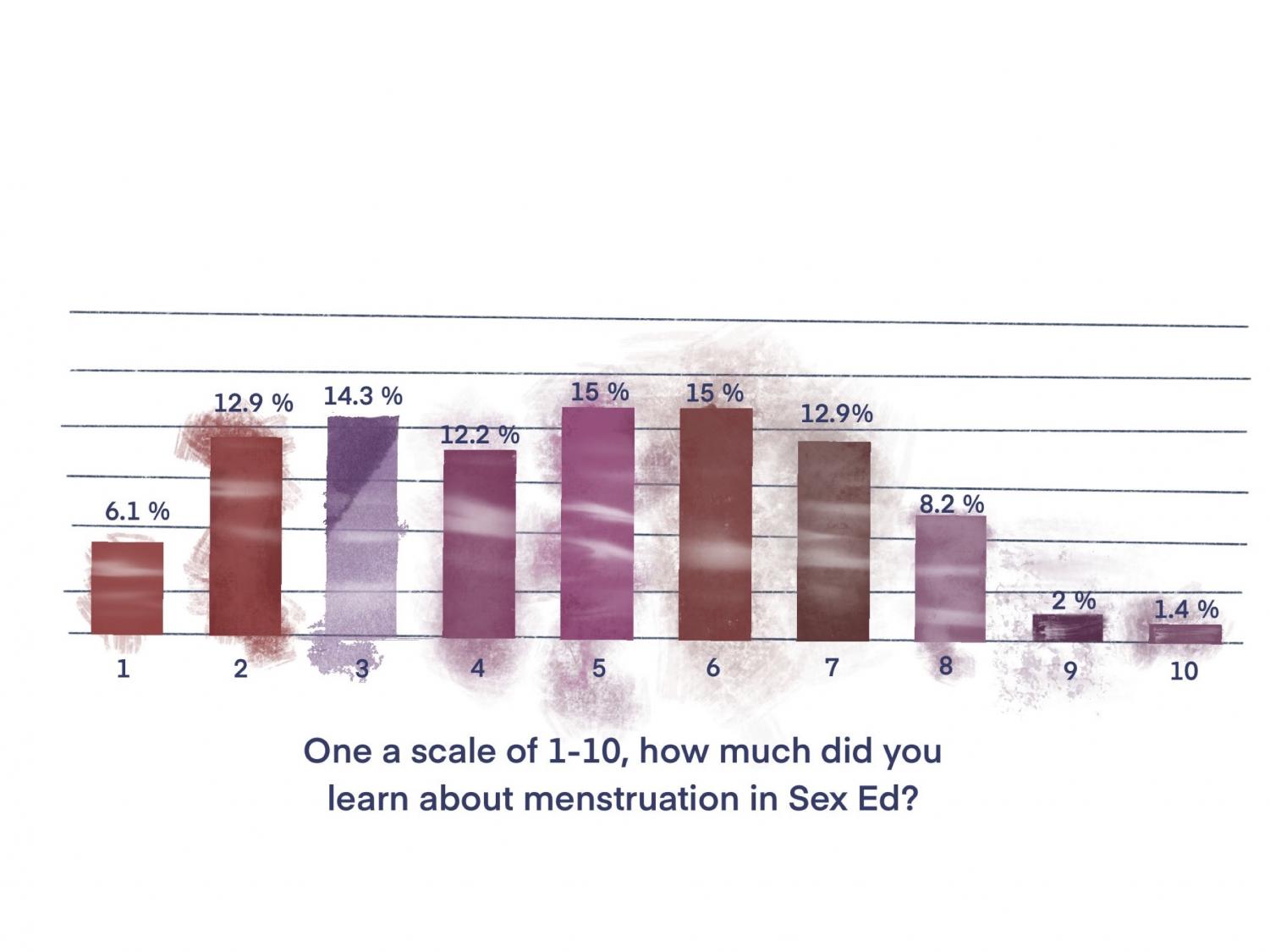

Later in the survey, students were asked how much they felt they knew about menstruation on a scale of one to ten. Seventy-five percent of participants answered with a five or higher which, based on the information given above on their knowledge of the menstrual cycle, is a slight inflation of the truth. About forty-five percent of participants, when asked how much they felt they learned about menstruation through sex-ed in school on a scale of one to ten, answered below a five. This statistic is more than enough to signify the lack of education or lack of impact sex-ed programs have made both throughout middle school and high school for students.

“I think I got [my understanding] from sex-ed and a mix of talking about it with people, but maybe some people aren’t paying attention. Maybe it wasn’t taught that well,” senior Casey Brandt said.

Menstruation happens after your body has been preparing for pregnancy and when no pregnancy occurs, the uterus sheds its lining. Menstrual blood is made up of blood as well as uterine tissue. One of the common misconceptions shown in the survey is that the purpose of menstruation is to become pregnant when in fact it is because the woman or person who menstruates did not become pregnant.

Women and those who menstruate have two ovaries that hold thousands of eggs. During menstruation, hormones such as estrogen and progesterone cause the eggs in your ovaries to mature. When an egg is mature, it is ready to be fertilized by a sperm cell. The release of these hormones causes the lining in the uterus to become thick. When the egg that has traveled through the fallopian tubes to the uterus and is not fertilized, the lining in the uterus breaks down, and the blood and nutrients built for pregnancy flow out of the body through the vagina. The reason why there is no period during pregnancy is that the body needs these tissues and nutrients to support a baby.

Additionally, while menstrual blood does exit through the vagina, it does not occur in the vagina.

To clarify a common misconception, the vagina is specifically the opening located between the urethra and anus where blood leaves the body from the uterus, babies are birthed, as well as the opening used for vaginal sex. The vaginal opening leads to the cervix and the uterus. The name for outer female genitalia is the vulva which includes the labia, vaginal opening, clitoris, and urethra. Menstruation occurs in the uterus, not in the vagina.

The last misconception is the concept of eggs. According to Cleveland Clinic, a nonprofit medical center, “At birth, there are approximately 1 million eggs; and by the time of puberty, only about 300,000 remain. Of these, only 300 to 400 will be ovulated during a woman’s reproductive lifetime. Fertility can drop as a woman ages due to the decreasing number and quality of the remaining eggs.” Menstruation can begin from about ages 11 to 14 and will continue each month until about the age of 50.

“I remember my friend said ‘I didn’t know it ever stopped’ like she just thought it went on through old age and I was like ‘I didn’t know it ever started,’” senior Talia Smith said.

For some, sex-ed is first introduced in elementary school during Puberty-ed or Family-ed. “I remember in fifth grade at Tam Valley, going through sex-ed and being like really confused,” Smith said. “They briefly brought it up and I remember learning about boys’ erections and everyone learned about that together and then they separated girls for periods which was like, in retrospect why couldn’t we learn about periods together? That was the first I had ever heard of it ever and I was really confused because the sex-ed teachers tried to dance around it because I think they assumed all the girls knew what it was, but I had no idea so I was listening and they were vaguely describing this thing.”

Tam is made out of many feeder schools, each with a different approach of sex-ed. Students who attended The Bolinas Stinson School report taking a sex-ed course every year of middle school with an instructor. Similarly, the same instructor came to Mill Valley Middle School to teach sex-ed to the eighth grade science classes. Through this course, students were educated on symptoms and transmissions of Sexual Transmitted Diseases as well as the different forms of contraception. Freshman Grace Porter, who attended MVMS, felt that while sex-ed was effective, it was not effective for learning about menstruation.

“I did take sex-ed in middle school. Honestly, it was mainly about STDs and safe sex, which is good, but I wanted to learn about periods because I’m not too informed. I did not learn about menstruation,” Porter said.

At Bayside MLK, sex-ed was taught only in fifth grade. “There wasn’t really sex-ed, it was only back in like fifth grade, it was only about puberty and stuff,” Senior Nimai Hammari said. For Marin Country Day School, sex-ed was taught in fifth and eighth grade.

In some schools, sex-ed was taught separately for girls and boys. “I don’t think guys are educated enough on the topic, I’m not even sure if they learned about it in fifth grade when they would separate the boys and girls for puberty-ed,” an anonymous female senior participant wrote on the survey. “Girls are taught that we have to keep it discreet and shouldn’t openly talk about it, it creates a lot of unnecessary shame around periods.”

At St. Hillary’s sex-ed was taught in sixth grade for three weeks where males and females were separated. For the girls, they spent three weeks learning about menstruation and abstinence. Similar, at Marin Montessori, the girls and boys were also separated.“There was a weird aura about the whole discussion. For the girls, we only talked about menstruation. We never talked about sexual assault and barely anything about sex,” senior Piper Rutchik said, who attended Marin Montessori.

“Basically their sex-ed was traumatizing. We only had ‘talks’ and it was like once a year and they devoted three hours to it and it was super uncomfortable…They split up the guys and girls which was the stupidest part about it because guys need to learn about us … I mean they were helpful but everyone tuned because they way they organized it was we had a ton of anonymous questions but the girls didn’t have a ton of questions and the guys took it as a joke.” Rutchik said.

At Tam, freshmen are enrolled in Social Issues where they have a gender and sexuality studies unit. During this sex-ed unit, while menstruation isn’t the main topic, “It was included when discussing birth control options but was not the main focus of a lesson,” Social Issues teacher Arielle Lehmann said. “The topic of affirmative consent is returned to after ninth grade, but the basics of sex-ed are not.”

Many students, however, remember very little from this course or don’t remember taking it at all. “I can’t recall learning [about menstruation] in high school, so I think I mostly learned it in eighth [grade] in sex-ed from Ms. Devine,” Brandt said.

Even through these years of sex-ed for students, the evidence is clear that there is not a full understanding of the process for students, including those who menstruate. “I didn’t learn much about periods or not that I can remember but I learned it happens for a week once a month,” sophomore Eliott Spencer said.

“I really do not know [why sex-ed refrains from talking about menstruation[ because it’s one of the most important parts so it’s really strange that they would refrain from learning about it. Learning about sex-ed you’re supposed to be learning about the basics: anatomy, protection, how your body works, so I feel like its a really important part,” Harkins said.

For many, menstruation is taught for the last time in middle school. “Obviously people aren’t going to remember what they learned in fifth grade or eighth grade so you need to keep brushing up on it,” senior Emerson Rabow said.

Concurrently, entering high school comes with a shift in social scenes that benefit from being educated on safe sex, contraception, and affirmative consent. “The most common high school year for people to start having sex is sophomore year, so getting some information before that becomes paramount. After that, there are so many things to learn that we simply don’t have time for everything,” Social Issues teacher Luc Chamberlin said.

However, even if menstruation is covered, it is not truly absorbed or understood by many due to lack of care, attention, or detail. “I definitely feel like if you’re a girl and you don’t really care that much you can just be like ‘I have a thing, it happens, whatever.’ I’m not saying that’s wrong but if you’re in eighth grade. You’re in the sex-ed unit, and you’ve already had your period for two years. Why do you care [about] the reason?” Smith said. “I don’t think it’s good to tune it out, but I understand why they might. But overall I think it’s good to have an understanding of what your body is doing.”

In part because of this lack of understanding or perhaps lack of education, the stigma against periods remains intact. “I think [it would be more uncomfortable] because [boys] don’t get it because obviously it’s way more normalized to talk about it with girls but also if I brought it up they wouldn’t be like ‘ew gross’ but I think a lot of boys would have that reaction. And if you don’t have a period I kind of understand why you would have that reaction,” Smith said. This aspect of periods being considered “gross” came up frequently, especially within the survey.

“I do think people are scared to talk about them because they think they are gross. I think people need to learn that periods are not gross and it’s normal to have them,” said Porter.

“There are so many misconceptions about how women act on their period and how to treat women on their period,” Rutchik said. “You shouldn’t treat us any differently. There are also ‘oh that’s gross and unsanitary’ and women are supposed to be these clean-cut, nice and perfect figures … You just bled through your pants and that doesn’t meet the angelic view of a female.”

While periods being viewed as ‘gross’ had been an assumption all along, it became more than clear through the anonymous responses to the survey. Below are some of the many recorded anonymous responses from Tam participants on what creates the stigma around periods:

“I think it’s mainly stigmatized because it’s a ‘Women’s issue’ and it’s been treated as this gross thing for so long, that people feel weird talking about it. But periods are totally normal and should be normalized!! People who menstruate shouldn’t have to feel awkward talking about it.”

“They’re spoken about as if they’re something super gross when in reality they’re a completely normal aspect of life for females and they aren’t talked about enough. the reason boys don’t know as much as girls usually are because girls have to know. and we’re taught to almost hide it and be embarrassed by it because it’s seen as gross.”

“Men. In my experience, women don’t have issues talking about it and actually welcome those conversations but because men are uncomfortable women have to be silent.”

“Because no one ever talked about it when growing up.”

“Because they think it is gross to hear about blood coming out of a Vagina.”

“They are seen as disgusting.”

“Because they aren’t normalized enough. Men need to be educated about menstruation so girls [do] not feel uncomfortable about bleeding through or changing their tampon or even talking about it.”

“Because they bleed out of their vagina.”

“Blood and vaginas.”

“Because some men (and sometimes women) use periods to degrade and embarrass women. i don’t feel awkward talking about my period.”

“Men want women to feel awkward and ashamed about their bodies. it makes them feel powerful to make women shameful about something they can’t control. it also allows taxes and high prices on period products because we are too embarrassed about it to stand up for what is right.”

“Because blood and vaginas are two words people (typically men) don’t like to put together in a sentence.”

“Might be uncomfortable for people because it’s a bodily fluid and some people might think of it as a controllable thing but you can’t control it so you shouldn’t be afraid to talk about it,” Brandt said.

“I know for certain countries and religions it’s a time for women to hide it or a time that makes people see women just as fertile not people. In the U.S, there isn’t anything like that, or if there is it isn’t the majority. It’s just uncomfortable because it’s just what is happening to your body,” Rutchik said.

However, through the years the subject of periods has become more and more normalized. “It is [taboo], but I believe it is less so when compared to when I was in high school,” Lehmann said. “Menstruation is still considered an ‘unpleasant’ topic to discuss/bring up with others. But at the same time, this generation of students is more forward-thinking. I have noticed a welcomed shift toward being more open about topics like menstruation.”

Hopefully with this shift in mindset will come alongside a shift in the sex-ed system bringing up discussions about the natural processes of the body alongside a more in-depth understanding of sexual wellness.

Our lack of education through sex-ed has created an awkward and, at times, shameful environment for talking about periods. Destigmatizing menstruation is not the job of one demographic and is especially not the job of the menstruator. It is our collective job as a society. Like many mental health and body positivity topics, keep an open mind during conversation, and be respectful. Through conversations and potentially a more in-depth education in sex-ed, ending the stigma is possible.

Period.