Tent City

(Savanna Behr)

Oct 24, 2021

If you walked by the tent encampment at Dunphy Park earlier this year, you may have heard Jesus, a name he chose, strumming his guitar and singing. Maybe you would have watched the Admiral Taylor, another nickname, barbequing or Peter Romanowsky leading a sermon. The encampment has many names; Camp Jesus, Camp Unity, Camp Rainbow Bay. Romanowsky had a few more names for it; “Camp Crazy, The Asylum, there’s a lot of the mentally ill, sometimes I call it Tent City. You can call it whatever you want,” he said. The founder, Daniel Eggink, called it “Sanctuary.” However, most residents called it “Camp Cormorant” after the bird native to the Bay Area. Throughout the camp are pride flags with spray-painted on cormorants.

Residents of the camp protested weekly all last year in attempt to remain there. But were moved in late June. “We aren’t done protesting because we’re here [in Marinship Park] we’re still going to be protesting the violence against anchor-outs. A lot of people here are victims of this war, the war going on against anchor-outs. Anchor-outs, generally, are people who live on boats anchored in the bay year-round. They’ve [homes on the bay] been here since before there were houses in Sausalito,” camp resident Micheal Ortega said.

During protests, residents of the camp chanted, “Camp Cormorant!” “You have to say it right. At the protests, everyone’s yelling. So that you can hear, you say ‘Cormorant!’” Taylor said.

Since the camp’s creation in late December last year, the city of Sausalito had been trying to remove it. Most of the residents of Camp Cormorant were anchor-outs who lost their boats and, with them, much of their belongings, according to an SF Chronicle article from June of this year.

Curtis Havel, appointed in Aug. 2019, accelerated plans that were already in place for decades but unenforced in order to “clean up” the bay. The anchor-outs had long since conflicted with the San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission (BCDC). The BCDC was recently criticized in a report Report 2018-120 by the California State Auditor for allowing 200 vessels to illegally anchor in Richardson Bay. That triggered the rapid removal of boats from the bay and the forming of Camp Cormorant.

On June 29, the Sausalito police cleared the camp, moving the residents to Marinship Park, only a few blocks away from their previous occupancy. The police were met with resistance in the form of protest. According to the Marin IJ, protesters of anchor-outs and other allies of the cause demanded to see a warrant and formed a line. They spoke through megaphones and took videos. The police ordered everyone to leave or be subject to arrest. Those who were moved into Marinship Park claimed it was full. Mayor Jill Hoffman denied this in a statement to the Mercury News in an article published in June, saying “We’ll evaluate what it looks like when the fenced area is nearing full capacity. We’re not there yet. I don’t think we will be there until we see who is where in the fenced-in area. Then we will adjust if necessary.”

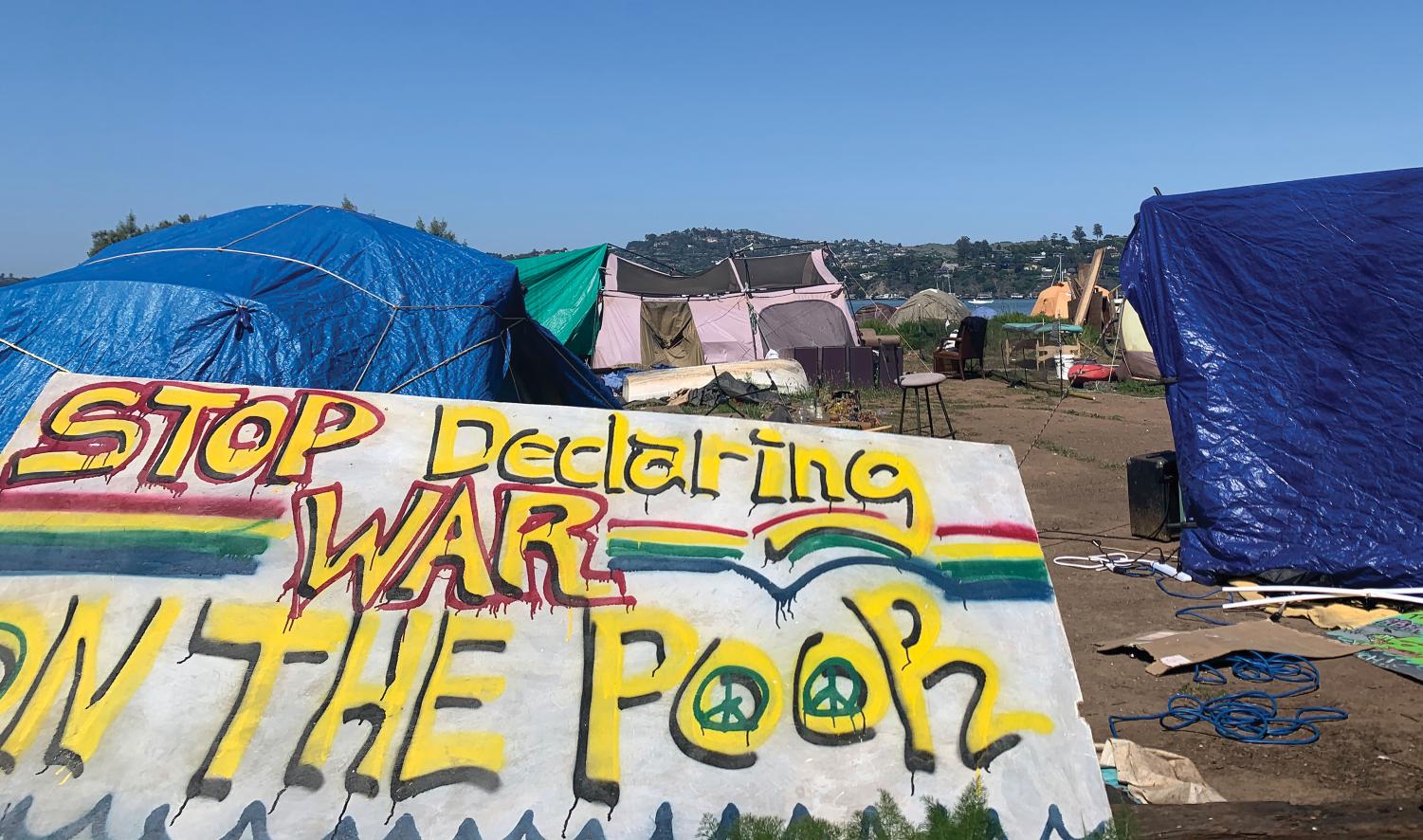

In the now relocated Camp Cormorant, there is a wall of painted signs, carried during protests. “[…]Curtis Havel crushed our boats,” and “End the war,” are some of the many signs displayed. There is also a structure with a roof of sticks and a tapestry as a back wall with a single chair in front, resembling a small stage. Besides the main tent and gathering area, there was a little kitchen with crates of potatoes, spices, utensils, eggs, and a grill in the back. When I visited, there were bags and bowls filled with more food. A wood plank with a recipe for “Rice, Rice, Baby!” was propped up beside the grill. The recipe called for chicken broth and one cup of rice.

Entering the main tent, made of tarps propped up by poles, I saw a whiteboard, couches, bookshelves, and a table in the middle. Art was everywhere, mainly done by Micheal Ortega, also known as “Mike The Artist.” Ortega graduated from Tamalpais High in 2007. He lived with his grandmother before moving to an anchor-out. One of his paintings, a colorful lion’s head, sat at the entrance of the camp. According to Romanowsky, Ortega is the “chief artist and architect […] He’s turned this place into an art camp. If there was a mayor, he’d be the mayor,” Ortega said. “I got a lot of tools, I help build, [and] I make signs for the protests.”

72-year-old Romanowsky has been an anchor-out for over 38 years. “I’m a minister, but I’m not an enforcer. I’m a spiritual leader,” Romanowsky said. Being the minister, he holds an informal church daily at Robin Sweeny Park in Sausalito. Romanowsky grew up in Marin and attended Redwood High. “Redwood ‘67! … We [Tam and Redwood High] hated each other back then. There were some really bad football games. We were rivals, you know? That was a long time ago,” Romanowsky said. Most of his congregation is fellow anchor-outs and who have the option of smoking marijuana during his sermon. “We’re a THC church!” Romanowsky said, “And I never made a profit preaching.”

Although he acknowledges that many members of the anchor-out community are mentally ill, he believes that they are as harmless as the rest of the Sausalito community. He regards them with empathy and acceptance which seems to be the entire camp’s general attitude. “You see babblers and yellers and screamers. It’s like primal scream therapy. There’s a lot of threats and bluster and bluff but it’s like a big family, there’s brothers and sisters fighting,” Rowanowsky said.

Ortega recounts the events of March 17, a clear reflection of the tensions between anchor-outs and the Sausalito government. His friend, Paul Smith, is an anchor-out who’d been on the water for years. He’s well known in the small community. Smith had a boat called the Warlock.

“Curtis had been trying to get his boat for months,” Smith said. Havel saw Smith wasn’t on his boat because his skiff was gone. He went and started towing it away. Smith fired a flare gun to call for help. The sheriffs came out to ask if he was armed. Smith showed the flare gun, in attempt to reassure them it was just a flare gun. But the sheriffs came back with two full boats of a SWAT team. “I wanted to help him […] We’re friends,” Ortega said. Later, smoke came from the boat and the boat somehow caught fire. The fireboat came, apparently, they had a problem setting up the hose. People watching were screaming at them to put out the fire. Finally, after it was maybe fifteen feet high, they put out the fire. His dog burned,” Ortega said. Smith’s dog died of smoke inhalation; Ortega’s story aligns with the one published in SF Weekly.

On the other hand, some residents of Marin felt decisive action was long overdue. “Cleaning up the Richardson Bay waterfront is a challenge, but doing nothing is not the responsible strategy for the environment and enforcement of reasonable laws,” an article published by the Marin IJ Editorial Board reads. In this article, Dick Spotswood of the Marin IJ referred to “ideologically based objectors clamoring to maintain unhealthy, unsafe floating slums on the public’s waters,” last February.

“The boats’ anchors, tackle, and other equipment can tear up the eelgrass, causing round areas of damage that resemble ‘crop circles’ as the boats move with the tide. Environmental damage also occurs in the form of oil and gas leaks, improper waste disposal, and crowding of the surface that drives away sea birds,” the SFGate said in 2019, acknowledging environmental concerns.

“We’ve had a horrible year,” Taylor said. “It’s really hard. I’ve been feeding people for years because this is a food desert! You can get a hotdog from 7-Eleven. Everywhere else nearby is 30 dollars for a little bit of food. I started barbecuing for myself when I realized if I spent ten more dollars I could feed a bunch more people. I’ll never serve ribs because when you’re buying ribs you’re buying bones! Try explaining what lobster bisque is to these crazy people while you’re warming it up!” Taylor said. Romanowsky said of his long-time friend Taylor, “He would stand on the freeway with a sign saying ‘always hungry,’ he’d make 20 dollars. Then he’d go down to Safeway and buy all the chicken he could. For 25 years! I saw him doing all this, even way before Cormorant. I rented out a space at the library sometimes and we’d feed people there,” Romanowsky said.

Calling the anchor-out community “close” is an understatement. “They’re my family. You need some fuel? You’re stuck on the rocks? You call someone, they’ll call someone and someone will help you,” Rafeal Lopez, a member of the camp said. And former resident of a boat anchored in the bay. Originally from Los Gatos, Santa Clara, Lopez has anchored in the Bay for over ten years. He had to sell his house in the East Bay after the 2008 recession. “You have to keep tightening your belt, like ‘I don’t really need this, I can’t afford this,’ giving up more and more,” Lopez said. He and his wife separated a few years back. “Eventually she said, ‘Rafeal, I’m not having my babies on a boat,’ I said… give me a break. Anyway, she left. Was it hard? What’s that question? Yeah! Ha!”

Permanent members of the encampment collectively agreed the encampment is by no means a community of drug users yet there are those who do take advantage of the relative safety of the camp to use it as a place to use dangerous drugs. That minority population poses a threat to established members of the anchor-out community trying to live peacefully.

Lopez highlights the issue of drug use in the community. “We aren’t meth-heads. There’s kids here, families. We don’t do that. The little white boy meth-heads come up, though, [from San Francisco] and someone brings drugs from the city like once a week. Imagine being in your house, let’s say with your family up in Mill Valley for instance, and your next-door neighbor is a crazy meth-head. Meth-heads around you, yelling, won’t stop for a week. You can’t stop them and if you do, [they] come at you with whatever weapon they have in their hand. We have these nylon stockings for tents, literally, look at that—just nylon, right—and that’s all you got between you and the weather and some crazy asshole, right? There’s meth-heads in our house. That’s it,” Lopez said.

Meanwhile Mayor Hoffman said, “Frankly there are people in the encampment facilitating that behavior. I think if they’re concerned about people in the encampment. That are doing harm to themselves or others. They need to report that to the police,” Romanowsky said. However he maintains that if they do call the police, the wrong people may be arrested. Or, simply, nothing will be done. “They’ll lock us up, they [police] think it’s us being crazy. They don’t try to understand.” Lopez said, “We have to self-police here.”

While eccentric, the permanent members of the community haven’t shown themselves to be a hazard to Sausalito. No arrests have been made against them. Besides during protests for alleged obstruction of justice. “We know property owners around the encampment have reported an increase in vandalism and trash. We watch pretty closely. I know there is drug use there. I just don’t know what the level is,” Mayor Hoffman said.

“It’s been a model crazy camp!” Romanowsky said.

Lopez never discloses if he is or isn’t an addict himself, but he grew up around substance abuse. And he speaks with empathy and understanding.

“Once you’re so far down the meth-head path, it’s just super difficult to stop. I mean, you need to be properly, internally motivated to get rid of it. You can’t tell somebody ‘Stop it.’ You can’t. You can put him [in] to programs. But they [will] get out and go right to the crack pipe. They’ve got to break their heart. It’s the whole alienation where you’ve got to hit rock bottom where there’s no other place to go. You know what that does to you. You’re about to die. What are you going to do? You’re gonna either stop, or you’re gonna die. Right? They’re such powerful drugs. I mean, you don’t know what I know, you’re a kid. You’re going to learn someday what it does to people. I swear,” Lopez said.

When asked what he’d like to say to Havel and the residents of Sausalito that consider anchor-outs a hazard, Lopez said, “I would refer back to basic moral compunctions about compassion. It’s not us or them, right?”

Situations like these show how close and connected our Marin community is. If you attended Redwood Highschool in 1967, you may have done a science project with Peter Romanowsky. Did you go to Tam High in the early 2000s, maybe you played a game of basketball with Micheal Ortega. If you are a frequent guest at the No Name Bar in Sausalito, you might’ve danced with Rafeal Lopez. These connections are something to keep in mind, for the future of Sausalito.

This past year was long and hard for the members of Camp Cormorant. The camp’s dismantlement took a toll on the community’s morale as they strive to make a stable home in Sausalito. Nevertheless, the same community of artists, builders, families, and freethinkers are sure to remain an integral part of the town’s community for years to come. “We have to stand up for our freedoms here no matter what. They can move us, they can take our boats, but we aren’t backing down,” Lopez said.