Pipeline

Feb 23, 2022

Nationwide, Black students receive out-of-school suspensions at a rate four times higher than white students, according to data collected by the National Center for Education Statistics. Yet, the 2013 CDC Youth Risk Behavior Survey and numerous other studies on the topic concluded that white youth and youth of color do not show significant behavioral differences and are equally likely to “get into fights, carry weapons, steal property, use and sell illicit substances, and commit status offenses, like skipping school.” Racial and economic disparities in the juvenile justice system contribute to a cycle known as the school-to-prison pipeline, which is described by the NAACP Legal Defense Fund as, “The funneling of students out of school and into the streets and the juvenile correction system … depriving youth of meaningful opportunities for education, future employment, and participation in our democracy.” It has been widely acknowledged that this cycle disproportionately targets African American, Latinx, low-income, and LQBTQ+ students. Harmful systems of discipline in schools that punish children instead of supporting their social-emotional needs contribute to the school-to-prison pipeline by making students of color more likely to struggle in school, not graduate, and fall into the criminal justice system. A study in Texas found that students who have been suspended or expelled are three times as likely to fall into the juvenile probation system the following year and are more likely to not graduate high school. The problem persists well into adulthood: 40 percent of all prisoners do not have a high school diploma and African Americans are imprisoned at five times the rate of white Americans. By exposing America’s youth of color to harsher discipline and bias at a young age and not giving them support in school during adolescence, they are thrust into the criminal justice system. This process has been streamlined over many decades and is now replicated over and over in school systems that continue to rely on problematic disciplinary practices that directly contribute to the mass incarceration of Black Americans.

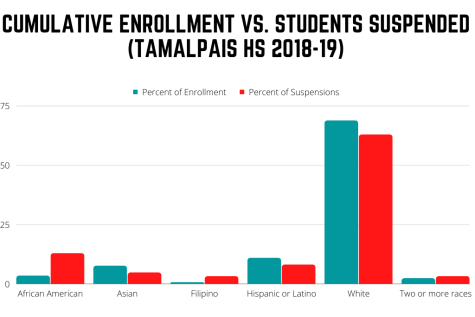

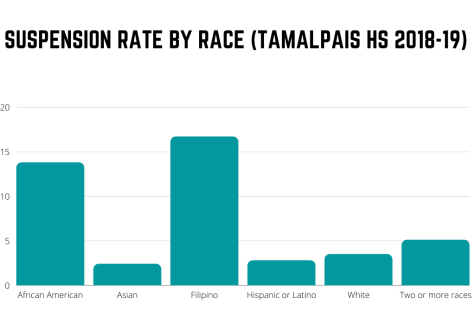

Although many harmful policies have been eliminated in recent years, inequities remain at the root of school disciplinary models that continue to perpetuate the school-to-prison pipeline. Marin County and Tamalpais High School are no exception to this. In the 2018-19 school year, the last year with reliable data due to the coronavirus pandemic, Black students at Tam were given out-of-school suspensions at nearly four times the rate of white students, comprising 13 percent of the 73 suspensions issued. This is despite accounting for only 3.5 percent of students— an overrepresentation of nearly four times their demographic in Tam’s overall population. That year, nearly 14 percent of African American students were suspended at least once, compared to less than four percent of white students. The school had an overall suspension rate of 3.8 percent, while the district- and county-wide suspension rates were 2.6 and 2.5 percent, respectively.

Restorative justice is a concept that has been around for decades, but it has recently emerged as an effective alternative to harmful and outdated disciplinary practices. It is based on indigenous models of discipline and “aims to reestablish the balance that has been offset as a result of a crime by involving the primary stakeholders (i.e. victim, offender, and the affected community) in the decision-making process of how best to restore this balance,” according to a 2017 analysis by the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. Many schools are beginning to adopt restorative justice in place of out-of-school suspensions and referring students to the traditional juvenile justice system. Districts that utilize restorative models devote time and effort to developing and maintaining trusting relationships among all members of the community. “Misbehavior is recognized as an offense against people and relationships, not just rule-breaking,” the San Francisco Unified School District noted on its restorative practices page. All staff are thoroughly trained in restorative practices in order to teach “a variety of communication skills, anger management techniques, and conflict management strategies.” The concept focuses on prevention; restorative justice is not just a response to misbehavior but rather the blueprint for an environment that fosters positive relationships and is equipped to address trauma that may lead an individual to cause harm before the damage is done. When an incident occurs, collaborative conversations known as “restorative circles” aim to address the root cause of the problem and repair the harm done to the relationship between the offender and the victim, parents, peers, teachers, and community. “Restorative plans” to correct wrongdoing are established in conjunction with the offender and are relevant to the harm caused, as well as the circumstances of the individual.

“It humanizes people and says that, ‘Even though you have behaviors that we don’t like, it doesn’t mean that we don’t like you.’ And it’s designed to break that school-to-prison pipeline,” former Tam Assistant Principal David Rice said. Rice, along with former Assistant Principal Leah Herrera and Special Education Resource Specialist Annacy Wilson, initiated a restorative justice program at Tam from 2016 to 2018. Wilson was the advisor to a club of students that acted as a peer jury, and the assistant principals referred students to the club as an alternative to issuing suspensions. “[Herrera] was the one who brought the student discipline and was able to say, ‘No, I think this student would benefit from a restorative approach.’ And that’s the way we did most of our discipline when I was there was through the restorative, especially if it was a first offense,” Rice said. The program petered out in 2018 when Rice, Herrera, and Wilson departed from Tam. “[Because] we’ve had a revolving door of administrators, we did not continue with developing our capacity to implement a full restorative justice program,” Tam Principal J.C. Farr said.

“We don’t really have a lot of suspensions and we have had very, very few incidents,” Farr said, noting that in 2020 Tam issued one suspension. “I think people may have felt … that there wouldn’t have been a great need for a restorative justice program [in 2020].” Rather than taking steps to re-implement a comprehensive program at Tam, Farr and the administration have partnered with a group called CircleUp, which provides staff training once per month in restorative practices. “I’m not sure at this point if it’s showing up in classrooms as a way of dealing with situations that are coming up in classrooms, but … we’re continuing to develop our capacity to do so,” Farr said. He added the administration is continuing to assess whether staff “see [restorative circles] as a viable strategy to address classroom communities and how students relate to one another.”

According to Farr, Tam teachers and administrators are becoming more familiar with restorative methods, but the conversations through CircleUp have not broken the threshold of talking about how implicit bias plays a role in school discipline and feeds the school-to-prison pipeline. “As we continue to build positive and strong relationships amongst staff, then that’ll allow us to have more conversations about bias, racism, institutional racism, and how it shows up in discipline, how it shows up in our interactions with students,” Farr said.

In the meantime, assistant principals at Tam are continuing with traditional disciplinary practices while attempting to pad suspensions with behavior counseling. “A suspension is a very serious consequence, but it’s not the same as being fined or potentially having a jail sentence or something like that out in the real world. So we want to prepare students for if there is something significantly damaging that they do, there are consequences for those actions, right?” Assistant Principal Connor Snow said. “And at the same time, we want to be able to teach them and help them repair that so that in the future, they can make a better and more informed decision.”

Restorative justice has shown promising results in studies, producing a decrease in suspension rates, narrowed racial disparities, and satisfaction among students and staff. A randomized controlled trial in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, collected data from 22 schools where restorative practices were used often by teachers, and compared suspension data with 22 controlled schools that did not use restorative justice. According to an analysis of the study by the National Education Policy Center, “the number of suspensions and days lost to suspension decreased more significantly in the [restorative justice] schools than in the control schools.” Specifically, days lost to suspensions fell by 36 percent in schools practicing restorative justice compared to 18 percent in the control schools. The study also observed that schools utilizing restorative justice had lower recidivism rates, meaning suspended students were less likely to be suspended more than once, compared to control schools. Schools in Oakland and Los Angeles where restorative justice models have been implemented also found that the suspension gaps between Black and white students narrowed, thus demonstrating how restorative practices have the potential to reduce the harm of the school-to-prison pipeline.

Marin County has its own program called Peer Solutions that uses restorative practices as an alternative to the traditional school and juvenile detention systems. The program is run under the organization Youth Transforming Justice (YTJ) and has been operating since 2004 using “peer-driven, restorative, and trauma-informed solutions” according to the program’s website. Adolescents who have been cited for misdemeanor offenses and taken accountability for their actions are referred to Peer Solutions, formerly known as Marin Youth Court, and, after completion of the program, their juvenile records are erased.

“The young person who has made the mistake is willing to be accountable for making that mistake, and not challenging the fact that they did make a mistake … they are willing to repair the harm and the relationships that that harm has impacted. Now, a lot of programs have adults facilitating that process. Our specialty at Youth Transforming Justice is having peers facilitate that process,” the program’s executive director Don Carney said. After a trauma-informed hearing facilitated by other youth who occupy roles such as jurors, facilitators, and advocates, respondents are assigned a case manager to support them through the process of completing their restorative plan.

All participants go through an intensive drug and alcohol training regardless of the circumstances that got them referred to the program. The training involves other peers as well as Associate Director Julie Whyte. Sacha Karaknofsy, who went through the program when she was a senior in high school and later became an intern for YTJ, described her experience with the training as “A very close, intimate experience … It really set something off in my brain because as peers, we don’t talk about drugs on the same level that we did in [the training].” Respondents are also offered extra support like tutoring and therapy and have the option to spend their community engagement hours doing something related to a personal interest such as volunteering for an animal shelter. Peer Solutions boasts a 95 percent completion rate and a six percent recidivism rate compared to the 75 percent juvenile recidivism rate nationwide, and has diverted over 1,300 teens from the juvenile justice system since 2004. “I see the change that it makes in people’s lives and I see the impact it has. I haven’t seen anyone that was too difficult to … get them to open up and share with us or learn something,” Karnofsky said.

Carney and Youth Transforming Justice also make themselves available as a resource to local schools, and welcome student referrals pro-bono as an alternative to suspension. The Tam administration paid Carney in 2016 and 2017 to train staff and students in restorative practices and help coach the program run by Rice, Herrera, and Wilson. However, the school has not referred one of its students to YTJ since November 2019. “Because of our differences, philosophically, I chose for Tam to withdraw our participation [from Peer Solutions],” Farr said. Farr declined to comment further on the philosophical differences between YTJ and the Tam administration.

Rice has continued to implement restorative practices in his administrative positions since leaving Tam in 2018, which included vice principal at Archie Williams High School and his current job as principal of Ross Elementary School. “Yeah, [restorative justice] is a much more laborious process of discipline than traditional, but the impact is longer term, and that’s why I continue to use it,” Rice said. “It is a lot more work upfront but issues tend to not come back.”

The school-to-prison pipeline continues to harm youth, particularly youth of color, at alarming rates. Restorative justice has been shown to drastically reduce suspensions and recidivism rates and provide youth with the tools they need to thrive in a school environment and the world beyond. These practices have succeeded at Tam when administrators, teachers, and students dedicate themselves to restorative justice. “I see it definitely expanding to everywhere … adults are blown away by this program and what it’s done and how it helps people and they’re like, ‘Why hasn’t this existed forever?’ It’s just really effective and it makes sense. So I don’t see why it wouldn’t expand immensely,” Karnofsky said.

Farr hopes the administration’s long-term partnership with CircleUp will eventually lead to the widespread adoption of restorative principles on campus that are immune to staff and student turnover. “I think the best case scenario is that teachers become more comfortable, and they utilize it as a strategy with their classes, and students and teachers see the effectiveness, then that will generate more interest to perhaps rebuild a club or develop some more consistent, sustainable efforts,” Farr said.