Wise beyond our years

May 2, 2023

A complete shutdown. Empty classrooms, students each separated by walls, and the threat of a contagious virus. We adapt to a drastically different life. The pandemic gradually slows down. Schools reopen, students are reintroduced to a strained sense of normalcy. Once again, we must regulate hormonally-altered emotions in one of the most tumultuous periods in a person’s life. We are back to navigating friendships, schoolwork, and basic aspects of school like rule-following and time management.

Naturally, this transition isn’t easy. Students struggled to acclimate first to quarantine, then the return to normalcy. This was evident in our behavior. However, the changes that students’ brains have suffered are worse than initially thought, because, as a recent Stanford Medical study revealed, this damage is reflected in physical changes. In other words, psychobiological damage impacts adolescent behavior on a deeper level than simply “struggling to adjust.” The striking fact is that the post-pandemic world is new territory: a worldwide study on psychological damage with no possible control group.

The House Is On Fire

The house is on fire. Teenager’s social, emotional, and academic development is struggling post-pandemic. While efforts are being made by the Tamalpais High School administration to provide mental health support, many believe more could and should be done.

The pandemic caused rapid maturation of adolescents’ brains. The Stanford study, titled “Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Mental Health and Brain Maturation in Adolescents: Implications for Analyzing Longitudinal Data,” compared the results of stress from the pandemic to the proven impacts of “violence, neglect, and family dysfunction,” which we already know cause negative cognitive changes.

The study consisted of 163 adolescents living in the San Francisco Bay Area. Initially, researchers were studying the effects of stress on psychobiology during puberty. Both brain-imaging technology and self-assessments were used. During the long-term study, it became clear that the pandemic had distinct effects on the brain functions being studied.

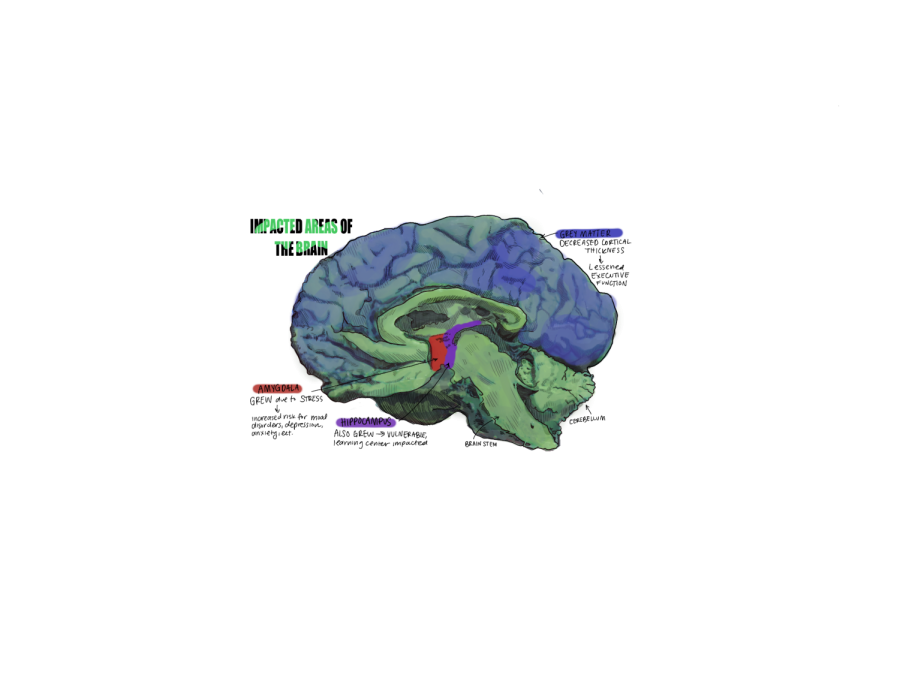

The post-pandemic group showed higher rates of severe internalizing mental health problems, reduced cortical thickness, larger hippocampal and amygdala volume. The physical changes signify advanced brain age. Reduced cortical thickness, a larger volume of certain brain parts, and accelerated brain maturation may not strike the general public as distinctly negative. Yet, these things are highly damaging in teens and are typically signs of trauma.

“We already know from global research that the pandemic has adversely affected mental health in youth, but we didn’t know what, if anything, it was doing physically to their brains,” Marjorie Mhoon Fair professor and director of the Stanford Neurodevelopment, Affect, and Psychopathology (SNAP) Laboratory at Stanford University, Ian Gotlib, said. Gotlib is the first author of the study.

Stress Changes the Brain

The field of stress research and especially its physiological effects is relatively very new. The earliest acknowledgement of stress in a scientific context was in the early 1900’s, when neurologist Walter Cannon first described the “fight or flight” response. In the study of an organ that, in many ways, remains a mystery, the Stanford study was crucial research.

“As a result of social isolation and distancing during the shut-down, virtually all youth experienced adversity in the form of significant departures from their normal routines. In addition, financial strain, threats to physical health, and exposure to increased familial violence were alarmingly common during the pandemic,” the study explains.

So how do these physical changes impact adolescents’ behavior? Reduced cortical thickness can cause increased impulsive and risky behavior, disturbances in attention span and memory, increased risk for psychosis, and even potentially lower IQs, according to various studies published in the National Library of Medicine’s National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) between 2013 and 2018.

The growth of the hippocampus and amygdala occurs naturally as people age. This growth is the result of an incredibly complex system about which little is known. However, in simple terms, increased activity in these parts of the brain causes them to rapidly grow more neurons, which is what happened to many of us.

The amygdala coordinates emotional responses to triggers, such as fear as a response to threats. But a larger amygdala early in life is associated with an increased risk for mood disorders like anxiety, according to a 2013 study also conducted by Stanford.

“The larger the amygdala … the stronger its connections with other parts of the brain involved in perception and regulation of emotion, the greater the amount of anxiety a child was experiencing,” the Stanford Medicine study states. This phenomenon also occurs in other animals.

According to a 2021 article published by the NCBI on the functions of the amygdala, this region of the brain plays a key role in both emotional processing and stress response. It processes a spectrum of stimuli from simple to complex interactions. The amygdala generates and processes not only emotions, but other types of signals like loss aversion, monetary loss, and actions with potentially negative outcomes. It is responsible for our perception, reward system, vigilance, attention, motivation, and ability to respond appropriately to situations. The amygdala also processes people’s more volatile emotions and responses, like aggression.

Like the amygdala, the hippocampus is evidently important for social, emotional, and academic development. Yet, little is known for certain about the specific functions of the hippocampus. Prominent theories often show connections between the hippocampus and regulating learning, memory encoding and consolidation, and spatial awareness. However, according to a study published in the Oxford University Press, we do know that the hippocampus is especially vulnerable to damage from things like seizures, head trauma, and stress.

Grey matter is one of the most significant parts of the human brain. Cortical thickness, which decreased while the amygdala and hippocampus grew, refers to the width of the cerebral cortex, a folded sheet of neurons with a width of usually a few millimeters. Many studies, including a 2020 study conducted by neuroscientists from Vanderbilt University and the University of Maryland show that the cerebral cortex is important for language, memory, reasoning, thought, learning, decision-making, emotion, intelligence, and aspects of one’s personality. The study concluded that when cortical thickness decreases as a result of “toxic stress” leads to greater cortisol release, the stress hormone, which lessens executive function. Toxic stress refers to any prolonged, frequent or severe adversity, which for many, quarantine was, as our brain physiology shows.

Out of the Frying Pan, Into the Fire

The pandemic exacerbated stressors in many areas of life, for all demographics of people. Students who relied on school as a social-emotional outlet and support system were forced to stay in abusive, unstable, and unsafe home environments.

The rate of teen mental health issues was increasing before the pandemic and has worsened post-pandemic, according to a press release by the Center for Disease Control (CDC) in March 2022. Put simply, things were bad before. Now, they’re worse. A summary of survey findings published in 2019 by the CDC further confirms this alarming truth. This survey showed that “persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness increased by 40 percent from 2009 to 2019 for U.S. high school students.”

Another 2022 press release by the CDC revealed that more than half of students experienced emotional abuse at home. One in ten percent experienced physical abuse by a parent or other adult in the home, including hitting, beating, kicking, or physically hurting the student. Nearly one in three percent reported a parent or other adult in their home lost a job.

However, marginalized groups were more heavily impacted. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and Black students were among the most likely to commit suicide during this period. According to a 2020 survey by The Trevor Project, a global nonprofit, 40 percent of LGBTQ+ youth seriously considered suicide in 2019. In 2021, the number hit 45 percent. When asked by the nonprofit, in 2020, to indicate which emotions described how they have been feeling since the COVID-19 pandemic began, the top three emotions experienced by LGBTQ youth were “stressed” (68 percent), “tired” (61 percent), and “nervous” (54 percent).

COVID-19 more severely affected people of color, LGBTQ+ people, and low-income people in the United States. According to an article published by the United States Census Bureau (CB), Black Americans had higher rates of “economic and mental health hardship.”

The CB compiled a list of reasons for this: insufficient housing, food insecurity, and an already higher risk of mental health problems like anxiety and depression. Black Americans are not the only group experiencing mental health problems as a result of the pandemic at a disproportionate rate. A 2020 study published by the CDC clearly reflected that people of color, women, LGBTQ+ Americans, among other marginalized groups, plus younger Americans in general, showed a decrease in mental health during and after the pandemic.

“I was depressed, it was one of the first times I’ve experienced mental health that bad. I think I changed a lot from [the Pandemic], in a way I know myself better now, I’m more close to myself in a way,” Tam senior Avi Perl said.

“[During COVID], school, for me, for the first time, became unmotivating and unstimulating,” Tam senior Eleanor Octavio said. Yet, like Perl, she also gained valuable skills, “Stress levels were definitely 10x higher after COVID, but to be honest, I came out of COVID with the ability to communicate with others so much more productively.”

The experience of being suddenly cut off from almost everyone we know and any sense of normalcy was like nothing else. There were negatives and positives, although that fails to capture the scope of the experience. It shaped us as a generation for better or worse. Now, it’s time to focus on how best to support adolescents in readjusting to a different life once again.

What does this mean for Tam?

Administration and teacher’s responses to a generation of students with rewired brains is something that should be handled with utmost care: the situation is complex, the research is new. These psychological changes were unprecedented and there’s really no protocol for a universally traumatized population, which is arguably what adolescents are suggested by these studies to be at this point.

There is a full spectrum of student opinion when it comes to the effectiveness and efficiency of administration and teacher’s responses, attitudes, policy changes, etc. Genuine efforts of teachers to support students post-pandemic rarely go unnoticed.

“What I’d ask for from some teachers and members of administration would be to be more understanding, maybe more respectful of our mental health and our needs when it comes to school. Just, sometimes a general sensitivity to students [experience] is needed,” Perl said.

Octavio agreed. She believes more sensitivity can and should look like concrete action. “Giving a little time for adjustment would be really beneficial. Also, putting increased resources towards Wellness and peer mentoring programs, since we are seeing more people needing to use these programs.”

However, on the other side, those in education must rapidly adapt to something for which there aren’t exactly guidelines.

On some level, the pandemic forced a pause in student’s overall social, emotional, and academic development. Teachers must learn to teach this population. Hopefully, all students take this into account, in the same way we hope teachers and administration acknowledge and continue to acknowledge our experience.

A 2022 press release by the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) provided statistics proving that the disruptions Tam has observed are occurring nationally and are a result of the pandemic. Fifty-six percent of public schools reported an increase in “classroom disruptions from student misconduct,” 48 percent reported an increase in “acts of disrespect towards teachers and staff,” and 49 percent reported an increase in “rowdiness outside the classroom.”

Student’s development within the classroom is suffering in a multitude of ways. We now know that the pandemic affected adolescents’ ability to focus, exercise self-control and good decision-making, motivation, emotional regulation, mood, memory, and even increased our risk for disorders like anxiety and psychosis, among other things.

But how do these changes actually look in a classroom setting?

Tam High’s teachers can certainly speak to the challenge of teaching post-pandemic. For some, these behaviors are on a very minor level, for others it is severe enough that teachers themselves experience burnout. According to an article that Forbes published this year, 90 percent of teachers experienced burnout.

U.S. History and AP U.S. History teacher Jennifer Dolan is alarmed with the amount of students that seem to be isolated and unfocused on a level she hasn’t seen in a long time.

“So I’m seeing much more of students just like, standing up and walking across the room and starting a conversation while I’m talking. And they’re not bad kids, they just, it’s like, they haven’t been constantly reminded of how we have to act, when we’re in a small group of people are, like in a classroom setting,” Dolan said.

“I think a lot of people got used to teachers being pretty easy graders, because everything was just so up in the air. But as teachers returned to a level of, ‘this is what the work looks like,’ it’s very frustrating and scary for some kids. They go straight to like, ‘I can’t do this, it’s too hard, instead of, you know, demonstrating persistence and grit,” she said.

Dolan is also concerned that her current students may not be as prepared for the AP exam, in May, as her previous classes. She attributes this in part to an unwillingness to go beyond the bare minimum.

Dolan is a beloved teacher and widely considered a good example of someone who students respect enough to listen to.

“I think she’s an amazing teacher who really values her students’ well-being. She’s really caring and empathetic,” Gigi Schulman, current senior, said of Dolan and her classroom environment.

Being a teacher post-pandemic has proved difficult for Dolan regardless. “It’s just challenging me in ways I haven’t been challenged in a long time. You know, I’m having to kind of go back to things I had to try when I was a new teacher. Because classroom management is an issue now,” Dolan said.

As a teacher of 25 years, she doesn’t expect to have to consider these factors. She doesn’t think her students are bad kids, she emphasizes. However, she believes that core skills, from successful note-taking to a general respect for a classroom environment, need to be retaught.

Essentially, Dolan’s class is concerningly not interested in each other or in the material in the way pre-pandemic students are. She does believe that students who missed the second half, who are now seniors, did miss less crucial time in school than her current juniors. Her own past students, current seniors, speak to this.

“Her class was totally different from [how Dolan describes her present class], we weren’t quiet. We would talk about the stuff we were learning,” Cayden Alley, now Tam senior, said.

Abigail Levine, who teaches Strategic Peer Mentoring and Core English, also feels constantly challenged teaching post-pandemic. Like Dolan, she is also now having to consider behavioral issues and classroom management as well as her curriculum and student’s academic success.

Although she’s taught for twenty years, she also feels like a new teacher. With these new challenges, Levine emphasized the fact that she, like all educators, is teaching against a backdrop of mental health crisis.

“There is a more serious undertone to what happens, there’s so much pressure … students need to be reading, they’re developing their literacy skills, but also I don’t want students to go home and not sleep and be stressed and overly anxious,” Levine said.

These factors add an element of pressure to the job. Being a teacher has always been a big responsibility, but now, stakes seem incredibly high.

Levine believes that building positive relationships with students and explicitly teaching behaviors, especially to underclassmen, is crucial in helping students get developmentally back on track.

She thinks this process will be a collaborative effort between students and educators, “The world still expects people to show up and do school the traditional way. Maybe we need to rethink how we do things as educators, I feel that would look like a partnership between what students need to do and what we need to do in education,” Levine said.

Students and teachers alike seem to want clarity and structure dealing with the post-pandemic transition. As Levine said, “We’re all kind of acting in the dark a little bit.”

Yvonne Milham, Tam High’s Wellness coordinator, has worked in schools for the past two decades. One of Milham’s roles in the Wellness Center is to assist students in regulating overwhelming feelings, meaning, she sees students’ reactions to stimuli first-hand, constantly.

“What we’re noticing is that resilience is a lot lower. There are things that bring students to Wellness that may have not in the past. For example, people realizing maybe they’ve studied the wrong material in a test and not being able to cope with that. I’ve seen the reactions of students and they do seem different than past reactions,” she said.

She has observed that regulating after a student’s reaction has been triggered is also more of a challenge.

“We give students 10 to 15 minutes to regulate in Wellness. In the past, that was absolutely enough time, it takes students a lot more focus now.”

Milham also speaks to what it truly looks like when students miss multiple years of socializing.

“In the spring, students will come in curious about how to ask someone to prom, things that maybe just would’ve been more natural before,” she said. “You miss middle school, maybe even freshman year, you miss those moments. When we’re talking about dating, and asking people to dances and doing things like that, [school] is sort of preparation for adulthood and relationships.”

Dean of Student Success and history teacher Nathan Bernstein explained that teachers have the choice independently to acknowledge the pandemic at all.

“At least in my classroom, there was a lot of understanding and saying like, okay, we need to slow down and reteach stuff,” Bernstein said.

While this is something, it’s nowhere near enough to combat the severe, lasting effects of the pandemic.

So what do we do?

We are back in school, and many students are adjusting well, but just because quarantine is over doesn’t mean students aren’t experiencing lasting effects. Our mental health, and ability to succeed in school, socially, and later on in adulthood is struggling. It needs to be acknowledged and managed, as we don’t yet know whether the damage is irreversible.

Neurologically, our generation is different from teens born just a few years earlier. Our brains are older than our chronological ages, as emphasized in an article published by Stanford University, which goes in-depth on the uncertain future the study implies. It’s unclear at this point how these changes will affect us long term.

The house is on fire, and we want help. Teens are aware we’re struggling, and that can’t be argued. Many are afraid for our futures as students with potential neurological changes that we don’t yet understand scientifically.

However, this isn’t a death sentence for our ability to regulate, process, socialize, and learn. Not at all. The human brain, particularly the adolescent brain, is incredibly powerful.

“There is always hope – plasticity may be important in repairing or taking over function of brain areas affected by trauma,” Gotlib said.

The extent of human’s neuroplasticity, essentially our brain’s ability to rewire its structure, is also a relatively new area of study. Yet the small amount of research almost always reaches that same conclusion.

To summarize an article published by the American Psycological Association last year, while the teenage brain is highly vulnerable to negative change in stressful environments, that same system allows our brains to repair and positively rewire themselves in healthy, supportive environments. Our brains can be repaired at any age, yet in adolescence, we are primed to do this. This neural circuitry is arguably the teenage brain’s greatest strength.

We do not yet fully know what the brain is capable of when it comes to repairing pandemic damage. Yet we do know there are ways to effectively treat the results of other trauma, both on severe and minor levels. Bottom line, because of our brains miraculous ability to heal itself, there is undoubtedly hope.

As UNICEF’s title of their 2017 compendium on adolescent neuroplasticity states, adolescence is “a second window of opportunity.” The text clarifies that little is known specifically about applying neurological theories and findings to intervention, echoing what has been said by Gotlib and many others.

Teens are more prone to what the document refers to as “patterns of behavior” — where common habits and choices, such as less sleep, spiral into a highly problematic cycle. However, according to UNICEF, “it is crucial to understand that adolescence is also a window of opportunity for positive spirals – establishing healthy patterns of behavior, and social and emotional learning that can increase positive developmental trajectories.”

Although the situation is uncharted territory, it’s nuanced, complex, and relative, we do know for a fact that part of this problem can be solved simply by teens interacting with each other.

“It’s not all bad. Go talk to your friends, but actually talk to them. Be in a group and make eye contact, be impacted by what someone is saying. I will 100 percent say that hanging out with your friends and truly being there, sharing similar experiences, it’s great for your brain. I’m seeing positive change, in the last year, the teenage mind is very resilient. There’s a lot of change that can still happen,” Milham advised.

The pandemic was terrible in many ways. Teachers, students, and all people alike experienced brain changes and the strain of a disease infecting the world. We all deserve empathy as we repair and come to terms with this damage.

As people with developing brains, teenagers need support, these changes are not something we are equipped to handle ourselves. While we can ask for what we need, the responsibility is on the authority figures around us.

A responsibility to research teen development and to create systems and programs that support the issues we need you to understand we have. We need those trained to put out this fire to do everything possible not to create a generation marked by pandemic trauma and further drag on this incredibly challenging period of history.